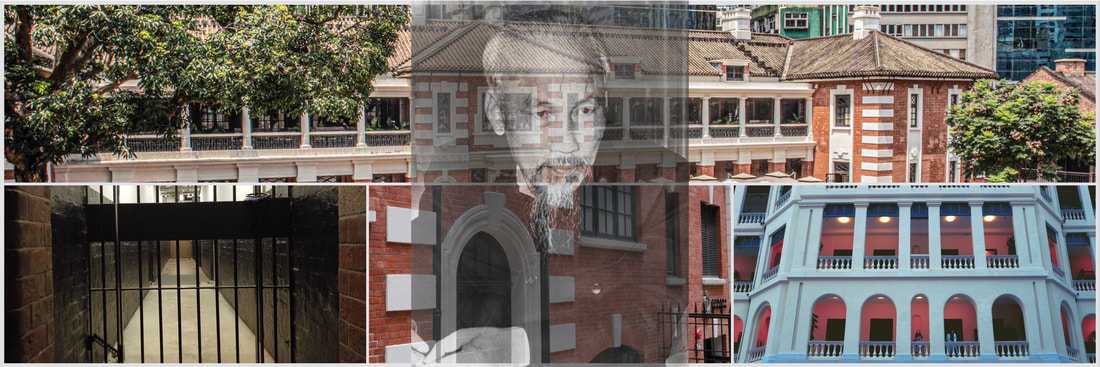

As you enjoy a G&T in the Tai Kwun compound raise your glass to Uncle Ho Chi Minh. In 1931, the grand master of the Vietnamese revolution resided here.

How he came to be in Tai Kwun is a complex story somewhat shrouded in myths, mix-ups and rumours. These include a faked death, an alleged escape from prison and dark tales of a spy exchange.

Throughout the 1920s, Ho went by the name Nguyen Ai Quoc. At the time, he was busy in China building the organisation that would eventually form the core of the communist league in Vietnam. He trained a cadre of revolutionaries to be sent home to spread the Marxist message.

The French authorities in Indochina (the later Vietnam) took a dull view of this activity. In October 1928, Ho was sentenced (in absentia) to death. Beyond the reach of the French and moving around covertly, Ho managed to sneak into Hong Kong in 1931, where he planned to meet with his people.

The French also had their people looking for Ho, and they soon identified his hideout in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Police arrested Ho on 6 June 1931 at a Kowloon house. He then pulled a double bluff. He refused to admit his true identity as either Ho or Nguyen Ai Quoc, insisting he is the Chinese national Sung Man Cho.

With insufficient grounds for an immediate extradition to Indochina, Ho entered Victoria Gaol on 12 June 1931, where he remained until 12 August 1931. On that day, he was handed to the Hong Kong Police for intended deportation on board a French ship. If carried out as planned, this action would mean death for Ho. By this stage, the evidence suggests the British authorities had a pretty good idea as to Ho's true identity, considering him a dangerous Moscow agent.

Then, a last-minute application of habeas corpus by lawyer Francis Loseby was able to delay the deportation. Following this, Ho made several court appearances to challenge the legality of his arrest while the Secretary of Chinese Affairs interrogated him to establish his identity.

When Ho appeared in the Supreme Court for the eighth time in ‘Sung Man Cho v. The Superintendent of Prisons’ on 11 September 1931, the Court ruled that the deportation order should stand. Yet, his lawyer immediately said he would appeal to the Privy Council in London. The Court agreed and held the deportation in abeyance.

But Ho suffered from dysentery, so he entered the prison hospital in November 1931.

The scene of action now moves to London. In June 1932, Ho's lawyers and the British Colonial Office settled the appeal case out of Court, with the Privy Council endorsing the decision on 21 July 1932. The settlement was a clever dodge.

The deportation order remained valid, but Ho would not be put on French ships or deported to Indochina or French territories. Instead, he's allowed to choose his destination with the help of the Hong Kong Government. He also received £250 for his troubles. There is a hint that British sensibilities baulked at the idea of handing Ho over to the French for execution.

Immediately Ho's lawyers began a disinformation campaign suggesting that he died in prison. This story spread through the newspapers and reached an international audience.

Then on 28 December 1932, Ho was secretly released from the prison hospital. A Cadet Officer attached to the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs received Ho, drove him to Kowloon and dropped him in the street. Rumours spoke of a spy swap. Yet, this is far from the end of Ho's adventures in Hong Kong.

He boarded a ship to Singapore on 12 January 1933 under the guise of a visiting scholar. But, on arrival, the British Singaporean authorities refused to land him. So Ho turned around, was sent back to Hong Kong, and was again arrested on 19 January 1933. By now, the Governor, Sir William Peel, became involved as the matter devolved into farce with potential embarrassment for the Colony.

Sir William arranged for Ho, accompanied by a law clerk, to be carried by launch to board the ship Anhui outside Victoria Harbour. The vessel departed Hong Kong on 22 January 1933. Stories spread that Ho had escaped or the Brits swapped him for a spy. The veracity of these rumours is unclear because the British wanted to get rid of Ho, yet they needed to appease the French. Fudging the matter helped.

Later in life, Ho Chi Minh documented his time in Hong Kong, describing the Victoria Gaol, "The building had three floors, with two rows of cells on each floor. Each cell was three yards high but only one yard wide and less than two yards long – with only enough space for a person to lie curled up. High above one's head was a small half-moon window covered with a grid of iron bars."

He observed, "The guards, Indians and British, pressed an eye to the peephole to check on the prisoner in the cell. The prisoners were allowed outside their cells for fifteen minutes to stroll around a narrow courtyard daily. Two meals a day of unhusked rice with stinky fish or soup was the norm. Each week, the prisoners received one special meal: a serving of cooked white rice and a few pieces of beef."

These days the dining at Tai Kwun is slightly more refined.

How he came to be in Tai Kwun is a complex story somewhat shrouded in myths, mix-ups and rumours. These include a faked death, an alleged escape from prison and dark tales of a spy exchange.

Throughout the 1920s, Ho went by the name Nguyen Ai Quoc. At the time, he was busy in China building the organisation that would eventually form the core of the communist league in Vietnam. He trained a cadre of revolutionaries to be sent home to spread the Marxist message.

The French authorities in Indochina (the later Vietnam) took a dull view of this activity. In October 1928, Ho was sentenced (in absentia) to death. Beyond the reach of the French and moving around covertly, Ho managed to sneak into Hong Kong in 1931, where he planned to meet with his people.

The French also had their people looking for Ho, and they soon identified his hideout in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Police arrested Ho on 6 June 1931 at a Kowloon house. He then pulled a double bluff. He refused to admit his true identity as either Ho or Nguyen Ai Quoc, insisting he is the Chinese national Sung Man Cho.

With insufficient grounds for an immediate extradition to Indochina, Ho entered Victoria Gaol on 12 June 1931, where he remained until 12 August 1931. On that day, he was handed to the Hong Kong Police for intended deportation on board a French ship. If carried out as planned, this action would mean death for Ho. By this stage, the evidence suggests the British authorities had a pretty good idea as to Ho's true identity, considering him a dangerous Moscow agent.

Then, a last-minute application of habeas corpus by lawyer Francis Loseby was able to delay the deportation. Following this, Ho made several court appearances to challenge the legality of his arrest while the Secretary of Chinese Affairs interrogated him to establish his identity.

When Ho appeared in the Supreme Court for the eighth time in ‘Sung Man Cho v. The Superintendent of Prisons’ on 11 September 1931, the Court ruled that the deportation order should stand. Yet, his lawyer immediately said he would appeal to the Privy Council in London. The Court agreed and held the deportation in abeyance.

But Ho suffered from dysentery, so he entered the prison hospital in November 1931.

The scene of action now moves to London. In June 1932, Ho's lawyers and the British Colonial Office settled the appeal case out of Court, with the Privy Council endorsing the decision on 21 July 1932. The settlement was a clever dodge.

The deportation order remained valid, but Ho would not be put on French ships or deported to Indochina or French territories. Instead, he's allowed to choose his destination with the help of the Hong Kong Government. He also received £250 for his troubles. There is a hint that British sensibilities baulked at the idea of handing Ho over to the French for execution.

Immediately Ho's lawyers began a disinformation campaign suggesting that he died in prison. This story spread through the newspapers and reached an international audience.

Then on 28 December 1932, Ho was secretly released from the prison hospital. A Cadet Officer attached to the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs received Ho, drove him to Kowloon and dropped him in the street. Rumours spoke of a spy swap. Yet, this is far from the end of Ho's adventures in Hong Kong.

He boarded a ship to Singapore on 12 January 1933 under the guise of a visiting scholar. But, on arrival, the British Singaporean authorities refused to land him. So Ho turned around, was sent back to Hong Kong, and was again arrested on 19 January 1933. By now, the Governor, Sir William Peel, became involved as the matter devolved into farce with potential embarrassment for the Colony.

Sir William arranged for Ho, accompanied by a law clerk, to be carried by launch to board the ship Anhui outside Victoria Harbour. The vessel departed Hong Kong on 22 January 1933. Stories spread that Ho had escaped or the Brits swapped him for a spy. The veracity of these rumours is unclear because the British wanted to get rid of Ho, yet they needed to appease the French. Fudging the matter helped.

Later in life, Ho Chi Minh documented his time in Hong Kong, describing the Victoria Gaol, "The building had three floors, with two rows of cells on each floor. Each cell was three yards high but only one yard wide and less than two yards long – with only enough space for a person to lie curled up. High above one's head was a small half-moon window covered with a grid of iron bars."

He observed, "The guards, Indians and British, pressed an eye to the peephole to check on the prisoner in the cell. The prisoners were allowed outside their cells for fifteen minutes to stroll around a narrow courtyard daily. Two meals a day of unhusked rice with stinky fish or soup was the norm. Each week, the prisoners received one special meal: a serving of cooked white rice and a few pieces of beef."

These days the dining at Tai Kwun is slightly more refined.

Copyright © 2015