History of HKP 1967 to 1980

"The Best Police Force Money Could Buy"

I wish I had a dollar for every time someone uttered the above to me. Late at night in a bar, encouraged by alcohol, crusty expats enjoyed goading the new arrivals. Although the truth was different. The syndicated corruption that had blighted the Hong Kong Police was over. Although incidents did flare up, none was on the scale of the events unearthed in the 1970s.

As Hong Kong shook off the events of 1967, the police force stood down from its anti-riot posture. It was a gradual return to regular patrolling. The force had earned the respect of the majority of the public for its steadfastness. In 1969 the title ‘Royal Hong Kong Police’ came from a grateful Britain.

Any credit attached to that epithet was about to diminish as corruption raised its ugly head. No discussion of Hong Kong’s history can ignore the role of corruption and the fight against it. The very structure and methods of the modern force evolved to deter bribery. Yet, in fairness, bribery in various forms existed across society. It's in the hospitals, schools and every sector of the civil service.

What is unique to the police is the large-scale syndicated activity. The scale of corruption was such that it provoked questions in London. MPs raised concerns in parliament. Unable to substantiate their claims with tangible evidence, it was easy to refute. In a contradictory position, it's asserted that corruption is a feature of Chinese life. They contended that rejected 'gifts' would offend the locals.

Yet a racket in Kowloon took bribes from mini-bus drivers to avoid traffic tickets. This was nothing to do with gifts. Until May 1970, this practice had existed in an ad-hoc manner. A TV documentary exposed money collected at bus interchanges across Hong Kong. Instead of stepping down, after a short hiatus, the involved officers switched tactics. They got organised.

In December 1971, the Tai Chow (Great Continental) Cleaning Company was set up out of an address in Mongkok. On the surface, the business offered cleaning services to mini-buses. Instead, drivers soon learned that paying $80 a week earned them a sticker. That gave freedom from traffic fines.

This despite a specific law prohibiting the display of stickers in bus windows. Drivers who failed to pay found themselves the focus of police enforcement action. One driver received three summons in four days. This is despite the fact his bus was off the road for repair.

Community leaders raised details of this racket and others with the Governor. The police run Anti-Corruption Branch tasked to investigate, arrested a few junior officers. The ACB, established in 1950, had a poor record. It never dug too deep.

Only token investigations took place. The public grew apathetic in the face of this official intransigence. Also, the media didn't sustain its efforts. No one in authority challenged the status quo.

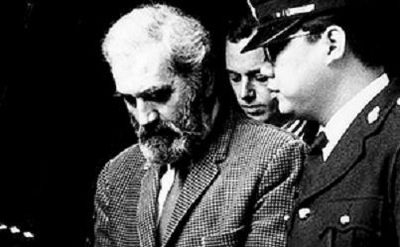

This changed with the Peter Godber case. Godber, a well regarded Chief Superintendent, played a leading role in 1967. In April 1973, information supplied to the Commissioner implicated Godber. An investigation by the Anti-Corruption Branch found HK4.3 million in an account. This being a sum six times his salary earned in 26 years of service in Hong Kong.

At an interview, Godber has one week to explain his assets. This provided a window of opportunity for him to flee. He was able to by-pass immigration checks using his airport security pass and board a plane on June 8 1973.

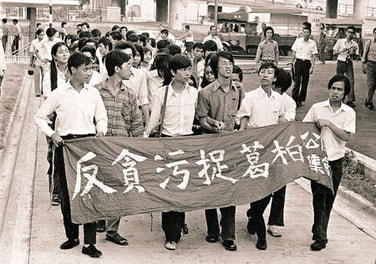

There is an immediate outcry from the public. Student groups mobilised in protest. Inflaming the sentiment was the fact that Godber appeared to be beyond the reach of Hong Kong law. He's enjoying his corrupt money in the UK. The suspicion grew that he's allowed to flee to avoid government embarrassment. As protests spread, some feared a riot. The Governor realising matters needed a quick intervention ordered a Commission of Inquiry. Three Judges then reviewed the police action and the related laws.

The Commission reported back after three months. It commented that syndicated corruption was rampant in the police force. Further, the enforcement of existing anti-corruption laws lacked any vigour. The Commission hinted at the formation of an independent body. Although, it never made a specific recommendation.

The Governor, Sir Murray MacLehose, then took opinions from various sectors. He resisted opposition from the Police Commissioner that anti-corruption efforts remain with them. He recognised that public sentiment was such that the status quo could not continue. In February 1974, the Independent Commission Against Corruption came into being. A stout leader and career civil servant, Jack Cater, led the ICAC. Godber returned to Hong Kong in 1975 to face trial and four years in jail.

In the early days, the ICAC relied on seconded police officers and overseas imports. The first job was to understand the scale of the problem. Thus action against syndicated police corruption only gathered pace in 1976. Cater was able to claim by July 1977 that he'd broken the majority of the syndicates. According to the 1977 ICAC Annual Report, a total of 7312 corruption reports came in. With 3519 cases investigated. This resulted in 749 persons prosecuted. The vast majority of those indicted were police officers.

The success of the ICAC did not go unchallenged, as a backlash from the police force rank and file developed. Some officers fled Hong Kong to escape the ICAC. Others accused it of unfair targeting by ignoring corruption elsewhere in government.

It is a fact that some junior officers had relied on corrupt money to supplement meagre police pay. With this source of income drying up and an economic downturn, officers struggled. Compounding the anti-ICAC sentiment was police suicides. Several officers fearing prosecution killed themselves.

Among the steps officers took including surrendering to the ICAC. These acts are indicative of the strength of sentiment as the situation escalated.

With its paramilitary structure and ranks, the force is not well placed to assess staff sentiment. Some of these limitations were structural, others cultural. A definite gap existed between expatriate seniors and the junior Chinese officers.

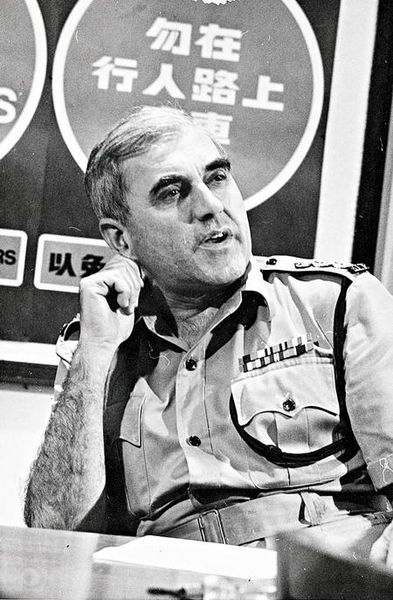

When poor morale get raised in the media, Commissioner Slevin responds with a denial. He send an assistant commissioner on TV to refute the assertions. Dismissed as whining malcontents, those making the allegations face discredit. Events are to prove Slevin and his team wrong.

In the autumn of 1977, things came to a head. The exact circumstances of the so-called, and misnamed, police mutiny remain difficult to pin down. While it’s certain juniors officers felt aggrieved at the actions of the ICAC. They also wanted a channel within the force to voice their concerns and aspirations. Most of all they wanted a fair hearing.

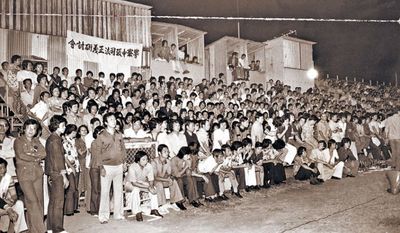

A petition is raised and attracts half the force to sign. Then on October 26, some 4000 officers gathered at the police club on Boundary Street. They voted to march on Police HQ the next day to seek a meeting with the Commissioner.

On October 27, thousands of officers marched through Central to gather near City Hall. The event caught the Governor unawares, as he drove past on route to a function. Reports suggest he's shaken to realise the magnitude of the police anger.

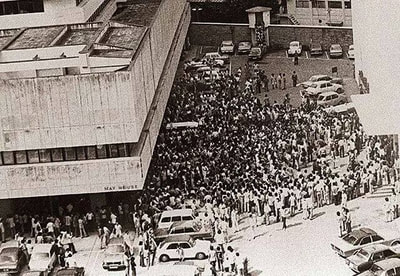

Later a large group of police officers gathered at Police Headquarters. Pictures show at least a thousand officers in the Arsenal Street compound. They sought a meeting with Commissioner Slevin.

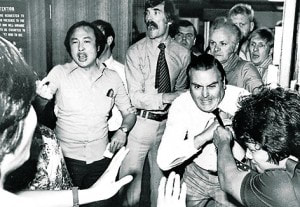

What happened next is subject to dispute. In one version of the day it’s said that Slevin declined to receive a delegation. He reportedly slipped away by a rear gate to avoid meeting the officers. In turn this inflamed sentiment. On hearing that Slevin had left, angry officers went to the nearby ICAC offices to pursue their claim. This action developed into a confrontation between the off-duty officers and ICAC staff.

Another version points in a different direction. Slevin or his deputy receives the delegation. A discussion takes place. It's agreed the Commissioner will acknowledge an association to represent junior officers. Delegates then brief the gathered off-duty officers, who gradually disperse. Except a breakaway group of hotheads goes to the ICAC headquarters.

What is certain is that a confrontation develops between the off-duty police officers and ICAC staff. With punches thrown and damage to property, the situation is out of control. Fear of a police mutiny spread as rumours take hold. Incorrect stories circulate that police units are failing to deploy.

The British military remained confined to barracks on standby. The situation is volatile. With typical decisiveness, MacLehose went on live TV. He announced a partial amnesty on 7th November 1977. In this announcement he stated;

“The ICAC in the future would ‘not normally act’ on complaints or evidence relating to offences committed before January 1977 except in relation to persons who had already been interviewed, persons against whom warrants had been issued, and persons outside of Hong Kong on November 5, and cases so heinous it would be unthinkable not to act.”

This bold and sudden step defused a crisis. In the process, it damaged the standing and morale of the nascent ICAC. Public confidence was also shaken. It appeared that the government was not serious about tackling corruption. Often overlooked in this saga is the power of police officers acting in unison. They had a realisation that they could bring about changes in policy. Future governments would be wary of this power centre.

The chattering classes felt the government had surrendered to the police. A few went as far as to suggest that the police held “a gun to the government's head.”

Media outlets asserted the police had mutinied. This grossly misrepresented the situation. Despite rumours to the contrary, police units did deploy as usual. I’ve spoken to many officers present during these events. With some strength of feeling they reject the charge that the police mutinied.

For many of the public, the die is cast with the amnesty. This blanket approach in its inadvertent sweep tars innocent officers. Disheartened many inside the force express shock at MacLehose’s actions.

Yet, the events of 1977, heralded many reforms. A review team from the UK, the so-called "Three WiseMen" made proposals for improvements. These changed the culture and structure of the force. Officers could form staff associations to pursue such interests as pay and conditions. Effective channels of communication opened between the rank and file to senior commanders.

This drive for open discussion was vital to defusing future crises. It gave the lower grades an opportunity to voice their opinions direct to seniors. As such, the filter of middle managers is gone.

Funds for sporting activities and clubs encouraged a healthy lifestyle. Pay and conditions underwent a steady improvement. These welcome changes were further embedded over time. Then public sector reform heralded an era of ‘quality service’ including for staff.

By the time I joined the Royal Hong Kong Police in 1980, the culture had evolved. Even a hint of malpractice would herald robust action. Frequent post rotation, integrity checks and monitoring lifestyles helped drive the process. Inspections on indebtedness identified vulnerable officers. These men are then removed from temptation.

At the same time, supervisory accountability brought managers to account. The excuse of ignorance or willful blindness didn't wash. Fundamental to this shift is officers having the courage to speak out.

With the primary battle against police corruption won, vigilance needed maintaining. Furthermore, as public expectations grew, officers faced new challenges. Wary that inappropriate behaviour could give rise to suspicions, habits had to change. Discouraged from smoking and drinking, those keen on promotion moderated their habits.

The late 1970s also saw an exodus of experienced officers as the force struggled to keep staff. Pay and conditions of service were part of the problem, although the atmosphere was poor. The conflict with the ICAC tainted things for some. With better prospects in other jurisdictions, men opted not to renew contracts. To encourage them to return, personal letters signed by senior management promised improvements. Policy changed to allow returning officers to keep seniority even after a protracted absence. As pay improved, a good number came back.

On crime, the 1970s marked a realisation that youth offences were growing. That would focus attention over the next decade. Meanwhile, the professionalisation of the police was gathering pace. In 1974, the Organised Crime and Triad Bureau came into being. Simultaneously, the Planning and Research Branch looked at best practices elsewhere. In a departure for a colonial police force, they studied aspects of US policing. In a gradual process, the foundations of ‘a customer focused’ approach came into being. Although the fruit of those efforts didn’t fully emerge until the 1990s.

As Hong Kong's population grew, the force expanded. That extra manpower would provide flexibility for the difficult years ahead. The challenges posed by Vietnamese boat people were starting to take shape. A violent crime wave was around the corner. Moreover, 1997 was now on the horizon.

I wish I had a dollar for every time someone uttered the above to me. Late at night in a bar, encouraged by alcohol, crusty expats enjoyed goading the new arrivals. Although the truth was different. The syndicated corruption that had blighted the Hong Kong Police was over. Although incidents did flare up, none was on the scale of the events unearthed in the 1970s.

As Hong Kong shook off the events of 1967, the police force stood down from its anti-riot posture. It was a gradual return to regular patrolling. The force had earned the respect of the majority of the public for its steadfastness. In 1969 the title ‘Royal Hong Kong Police’ came from a grateful Britain.

Any credit attached to that epithet was about to diminish as corruption raised its ugly head. No discussion of Hong Kong’s history can ignore the role of corruption and the fight against it. The very structure and methods of the modern force evolved to deter bribery. Yet, in fairness, bribery in various forms existed across society. It's in the hospitals, schools and every sector of the civil service.

What is unique to the police is the large-scale syndicated activity. The scale of corruption was such that it provoked questions in London. MPs raised concerns in parliament. Unable to substantiate their claims with tangible evidence, it was easy to refute. In a contradictory position, it's asserted that corruption is a feature of Chinese life. They contended that rejected 'gifts' would offend the locals.

Yet a racket in Kowloon took bribes from mini-bus drivers to avoid traffic tickets. This was nothing to do with gifts. Until May 1970, this practice had existed in an ad-hoc manner. A TV documentary exposed money collected at bus interchanges across Hong Kong. Instead of stepping down, after a short hiatus, the involved officers switched tactics. They got organised.

In December 1971, the Tai Chow (Great Continental) Cleaning Company was set up out of an address in Mongkok. On the surface, the business offered cleaning services to mini-buses. Instead, drivers soon learned that paying $80 a week earned them a sticker. That gave freedom from traffic fines.

This despite a specific law prohibiting the display of stickers in bus windows. Drivers who failed to pay found themselves the focus of police enforcement action. One driver received three summons in four days. This is despite the fact his bus was off the road for repair.

Community leaders raised details of this racket and others with the Governor. The police run Anti-Corruption Branch tasked to investigate, arrested a few junior officers. The ACB, established in 1950, had a poor record. It never dug too deep.

Only token investigations took place. The public grew apathetic in the face of this official intransigence. Also, the media didn't sustain its efforts. No one in authority challenged the status quo.

This changed with the Peter Godber case. Godber, a well regarded Chief Superintendent, played a leading role in 1967. In April 1973, information supplied to the Commissioner implicated Godber. An investigation by the Anti-Corruption Branch found HK4.3 million in an account. This being a sum six times his salary earned in 26 years of service in Hong Kong.

At an interview, Godber has one week to explain his assets. This provided a window of opportunity for him to flee. He was able to by-pass immigration checks using his airport security pass and board a plane on June 8 1973.

There is an immediate outcry from the public. Student groups mobilised in protest. Inflaming the sentiment was the fact that Godber appeared to be beyond the reach of Hong Kong law. He's enjoying his corrupt money in the UK. The suspicion grew that he's allowed to flee to avoid government embarrassment. As protests spread, some feared a riot. The Governor realising matters needed a quick intervention ordered a Commission of Inquiry. Three Judges then reviewed the police action and the related laws.

The Commission reported back after three months. It commented that syndicated corruption was rampant in the police force. Further, the enforcement of existing anti-corruption laws lacked any vigour. The Commission hinted at the formation of an independent body. Although, it never made a specific recommendation.

The Governor, Sir Murray MacLehose, then took opinions from various sectors. He resisted opposition from the Police Commissioner that anti-corruption efforts remain with them. He recognised that public sentiment was such that the status quo could not continue. In February 1974, the Independent Commission Against Corruption came into being. A stout leader and career civil servant, Jack Cater, led the ICAC. Godber returned to Hong Kong in 1975 to face trial and four years in jail.

In the early days, the ICAC relied on seconded police officers and overseas imports. The first job was to understand the scale of the problem. Thus action against syndicated police corruption only gathered pace in 1976. Cater was able to claim by July 1977 that he'd broken the majority of the syndicates. According to the 1977 ICAC Annual Report, a total of 7312 corruption reports came in. With 3519 cases investigated. This resulted in 749 persons prosecuted. The vast majority of those indicted were police officers.

The success of the ICAC did not go unchallenged, as a backlash from the police force rank and file developed. Some officers fled Hong Kong to escape the ICAC. Others accused it of unfair targeting by ignoring corruption elsewhere in government.

It is a fact that some junior officers had relied on corrupt money to supplement meagre police pay. With this source of income drying up and an economic downturn, officers struggled. Compounding the anti-ICAC sentiment was police suicides. Several officers fearing prosecution killed themselves.

Among the steps officers took including surrendering to the ICAC. These acts are indicative of the strength of sentiment as the situation escalated.

With its paramilitary structure and ranks, the force is not well placed to assess staff sentiment. Some of these limitations were structural, others cultural. A definite gap existed between expatriate seniors and the junior Chinese officers.

When poor morale get raised in the media, Commissioner Slevin responds with a denial. He send an assistant commissioner on TV to refute the assertions. Dismissed as whining malcontents, those making the allegations face discredit. Events are to prove Slevin and his team wrong.

In the autumn of 1977, things came to a head. The exact circumstances of the so-called, and misnamed, police mutiny remain difficult to pin down. While it’s certain juniors officers felt aggrieved at the actions of the ICAC. They also wanted a channel within the force to voice their concerns and aspirations. Most of all they wanted a fair hearing.

A petition is raised and attracts half the force to sign. Then on October 26, some 4000 officers gathered at the police club on Boundary Street. They voted to march on Police HQ the next day to seek a meeting with the Commissioner.

On October 27, thousands of officers marched through Central to gather near City Hall. The event caught the Governor unawares, as he drove past on route to a function. Reports suggest he's shaken to realise the magnitude of the police anger.

Later a large group of police officers gathered at Police Headquarters. Pictures show at least a thousand officers in the Arsenal Street compound. They sought a meeting with Commissioner Slevin.

What happened next is subject to dispute. In one version of the day it’s said that Slevin declined to receive a delegation. He reportedly slipped away by a rear gate to avoid meeting the officers. In turn this inflamed sentiment. On hearing that Slevin had left, angry officers went to the nearby ICAC offices to pursue their claim. This action developed into a confrontation between the off-duty officers and ICAC staff.

Another version points in a different direction. Slevin or his deputy receives the delegation. A discussion takes place. It's agreed the Commissioner will acknowledge an association to represent junior officers. Delegates then brief the gathered off-duty officers, who gradually disperse. Except a breakaway group of hotheads goes to the ICAC headquarters.

What is certain is that a confrontation develops between the off-duty police officers and ICAC staff. With punches thrown and damage to property, the situation is out of control. Fear of a police mutiny spread as rumours take hold. Incorrect stories circulate that police units are failing to deploy.

The British military remained confined to barracks on standby. The situation is volatile. With typical decisiveness, MacLehose went on live TV. He announced a partial amnesty on 7th November 1977. In this announcement he stated;

“The ICAC in the future would ‘not normally act’ on complaints or evidence relating to offences committed before January 1977 except in relation to persons who had already been interviewed, persons against whom warrants had been issued, and persons outside of Hong Kong on November 5, and cases so heinous it would be unthinkable not to act.”

This bold and sudden step defused a crisis. In the process, it damaged the standing and morale of the nascent ICAC. Public confidence was also shaken. It appeared that the government was not serious about tackling corruption. Often overlooked in this saga is the power of police officers acting in unison. They had a realisation that they could bring about changes in policy. Future governments would be wary of this power centre.

The chattering classes felt the government had surrendered to the police. A few went as far as to suggest that the police held “a gun to the government's head.”

Media outlets asserted the police had mutinied. This grossly misrepresented the situation. Despite rumours to the contrary, police units did deploy as usual. I’ve spoken to many officers present during these events. With some strength of feeling they reject the charge that the police mutinied.

For many of the public, the die is cast with the amnesty. This blanket approach in its inadvertent sweep tars innocent officers. Disheartened many inside the force express shock at MacLehose’s actions.

Yet, the events of 1977, heralded many reforms. A review team from the UK, the so-called "Three WiseMen" made proposals for improvements. These changed the culture and structure of the force. Officers could form staff associations to pursue such interests as pay and conditions. Effective channels of communication opened between the rank and file to senior commanders.

This drive for open discussion was vital to defusing future crises. It gave the lower grades an opportunity to voice their opinions direct to seniors. As such, the filter of middle managers is gone.

Funds for sporting activities and clubs encouraged a healthy lifestyle. Pay and conditions underwent a steady improvement. These welcome changes were further embedded over time. Then public sector reform heralded an era of ‘quality service’ including for staff.

By the time I joined the Royal Hong Kong Police in 1980, the culture had evolved. Even a hint of malpractice would herald robust action. Frequent post rotation, integrity checks and monitoring lifestyles helped drive the process. Inspections on indebtedness identified vulnerable officers. These men are then removed from temptation.

At the same time, supervisory accountability brought managers to account. The excuse of ignorance or willful blindness didn't wash. Fundamental to this shift is officers having the courage to speak out.

With the primary battle against police corruption won, vigilance needed maintaining. Furthermore, as public expectations grew, officers faced new challenges. Wary that inappropriate behaviour could give rise to suspicions, habits had to change. Discouraged from smoking and drinking, those keen on promotion moderated their habits.

The late 1970s also saw an exodus of experienced officers as the force struggled to keep staff. Pay and conditions of service were part of the problem, although the atmosphere was poor. The conflict with the ICAC tainted things for some. With better prospects in other jurisdictions, men opted not to renew contracts. To encourage them to return, personal letters signed by senior management promised improvements. Policy changed to allow returning officers to keep seniority even after a protracted absence. As pay improved, a good number came back.

On crime, the 1970s marked a realisation that youth offences were growing. That would focus attention over the next decade. Meanwhile, the professionalisation of the police was gathering pace. In 1974, the Organised Crime and Triad Bureau came into being. Simultaneously, the Planning and Research Branch looked at best practices elsewhere. In a departure for a colonial police force, they studied aspects of US policing. In a gradual process, the foundations of ‘a customer focused’ approach came into being. Although the fruit of those efforts didn’t fully emerge until the 1990s.

As Hong Kong's population grew, the force expanded. That extra manpower would provide flexibility for the difficult years ahead. The challenges posed by Vietnamese boat people were starting to take shape. A violent crime wave was around the corner. Moreover, 1997 was now on the horizon.

Copyright © 2015