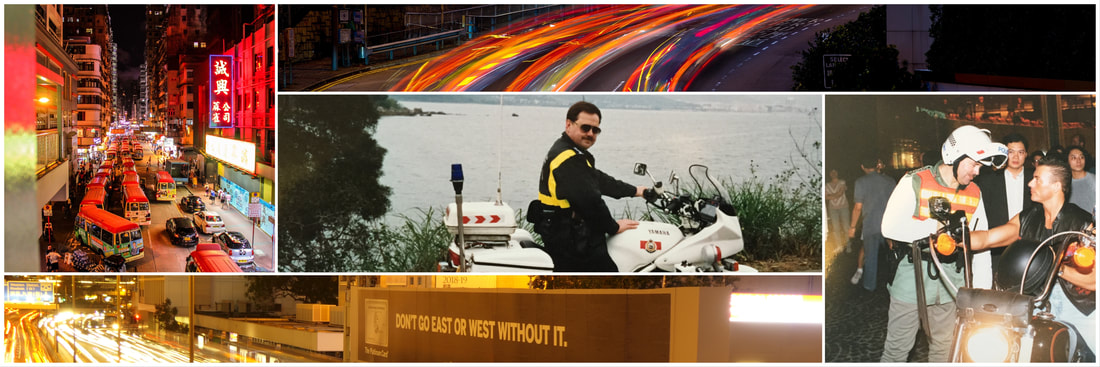

By 1992, the career development system computer went 'ping'. So, as part of my career development, I'm moving again to take charge of the "Traffic Kowloon West Enforcement Section". This job will see me leading 200 officers seeking to keep things moving on the peninsular.

In this thankless task, I'm up against too many vehicles, poor infrastructure and inadequate parking. The geography doesn't help.

Tsim Sha Tsui is a natural bottleneck; the Cross Harbour Tunnel helps create daily tailbacks. Added to that is the ongoing construction work — as the joke goes, Hong Kong will look nice when it's finished!

The disconnect between what we could achieve and public expectations always vexed me. Nobody cares except that they can move about as quickly as possible and park anywhere. I soon learned that people in flash cars are selfish and entitled.

"Why isn't the traffic moving?"

"Because it blocked, Sir"

"Well, do something about it. I pay your wages." I have heard this phrase thousands of times.

Smile back while inside, thinking, "Work harder. I need more money."

For the most entitled who persisted a quick, "You appear to have a modified car, Sir. Do you have permission from the Transport Department for that spoiler? Please pull over up ahead."

That usually did the trick—not that I did it often. I'm not a vindictive individual, but some people need their self-entitlement deflated.

For most of the week, we spent our time trying to keep the traffic flowing. But come the weekends, the game changed. In a bizarre twist, our aim changed to slowing traffic flows on critical roads to defeat the illegal road racers—more on that in the next chapter.

My office is in the old Mongkok Police Station. The building dates from the 1920s and has creaking floorboards, high ceilings, and a distinctive colonial feel. I even have a fireplace in the office.

By now, I'm well versed in the etiquette of taking over a new unit. Rule number one: don't rush in and change things. The worst approach is to get all innovative without understanding the place's history.

Further, as the 'Chief Inspector of Enforcement and Control', I'm told my job is out on the streets. That suited me. Still, I already knew that keeping the traffic moving was an impossible task. We did what we could, which had a marginal impact at best.

My daily routine involves attending major traffic accidents, especially the deaths—they are never pleasant. I also lead operations against illegal taxis and tampered meters and deal with other traffic matters.

I am fortunate to have a competent crew of inspectors and station sergeants. The latter, who'd spent most of their careers in traffic, are the unit's backbone. I'm passing through in what will be a two-year posting, so it's always wise to take their counsel.

Most working days start with a meeting — morning prayers look at the last 24 hours to clear up outstanding issues and answer questions coming down the chain of command. Some bosses get triggered by exaggerated media reports with photographs taken out of context or commentaries based on misunderstandings or outright lies. It's a constant battle addressing this stuff.

Few things irked me more than the inane questions a moment of reflection could answer.

"Why was an officer not wearing his headgear at the traffic accident?"

"Well, because the press photographer caught him when he switched from his helmet to a soft cap."

Sometimes, the problem was intermediate commanders evoking the Regional Commander's name.

I caught out a superintendent who'd asked, "What was the delay in opening Canton Road?" he called to ask after a bus accident, "The boss wants to know."

Having got my answer, I couldn't reach the slippery super, so I called the boss directly.

"What are you talking about?" he snapped. I told him. Pause. I could hear his breathing down the phone.

"Mmmm. Leave that with me." I'm sure I wasn't winning friends.

After prayers, I'd undertake a quick patrol to show my face. Of course, the number of incidents drives the front-line officers' workload: accidents, road works and reports of obstructions. But, you could spend all day taking enforcement action and still only have a small impact.

There is no glamour in riding a 750 cc motorcycle around Kowloon. Picture this: heat, humidity, road crud, diesel fumes, and inattentive drivers combine in a tiring mix. Then along come downpours that turn the road surface into a skid pad. As the saying goes, "There are two types of traffic officers: those who had an accident and those waiting to have one."

Still, there were moments of excitement. Matters took a surprisingly dramatic turn in May 1992. Anita Mui, the "Madonna of the East", held her birthday party in a Kowloon karaoke club when trouble kicked off. She'd declined to sing with Wong Long-wai, a 14K triad member and movie producer. Having lost face, Wong slapped her.

The following evening, somebody slashed Wong in Wan Chai. One of the alleged assailants, Andely Chan Yiu-hing, also known as "the Tiger of Wan Chai", was a Sun Yee On triad. He and Mui had a close friendship. Chan also fancied himself as a race-car driver, so he was on our radar.

Two days later, recovering in hospital, someone walked in and executed Wong with a single shot to the head. Anita Mui immediately fled Hong Kong.

Trouble brewed between the 14K and Sun Yee On throughout 1992 and much of 1993. In response, the Regional Commander asked how units could help with a broader effort to disrupt the gangs. While traffic officers aren't usually involved in the direct fight against the triads, that was about to change.

A brainstorming session with my lads produced a couple of options. The boss agreed to our proposals. We'd start towing all the triad vehicles we could find illegally parked and set the motor vehicle examiners to work. Soon, CID provided a list of cars and locations. Off we went.

We began a disruption campaign at the scene of the initial incident in Kowloon Tong. We'd muster as many tow trucks as possible, wait for the triad boys to settle in the club and then start towing their cars. To keep the pressure on, we did this night after night. We bagged 42 cars one night, leaving their owners to find taxis.

When one of the tow truck drivers received threats, we identified the group responsible. They operated a repair shop in Tai Kok Tsui. For the next week, we visited them to ticket and tow anything outside their workshop. They needed to understand actions have consequences.

We later shifted focus to the Tsim Sha Tsui East area to disrupt the business of the triad car jockeys outside the nightclubs. The night before a public holiday or over a long weekend, we'd deploy 100-plus officers.

These tactics hit the triads in the pocket by discouraging their punters. Also, they struggled to move around as we hauled their cars away.

Occasionally, things became heated at the Homantin vehicle pound as the owners demanded their cars back. With 30 agitated drivers yelling at the pound staff, we'd front up with a PTU platoon in tow to ensure everyone behaved. The smart ones would keep their mouths shut, pay the impound fee and get their car back.

The less savvy drivers took to making a scene. That's silly, given that most had illegal modifications on their vehicles, which gave us the discretion to detain their cars. We ran this operation until late 1993. It was tiring and manpower-intensive, with overtime payments pushed to the limits. Yet, we'd made a point.

As Andy Chan remained a suspect in the murder of Wong, he kept a low profile. Then, on November 20, 1993, he finished second in the Macao Grand Prix but faced disqualification for modifications on his car. The following day, Chan died in a hail of bullets as he exited his Macau hotel. After that, things settled.

Some light relief came in 1994. On May 30, Hollywood came to Hong Kong. The opening of the movie-themed restaurant 'Planet Hollywood' was shaping up to be the night of the stars. A few A-listers are Sylvester Stallion, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Glen Close, Charlie Sheen, and Jackie Chan.

It was soon recognised that this lot would attract a considerable crowd that needed to be managed with road closures. The restaurant, sited on Canton Road, was the main focus, although many stars stayed at the nearby Regal Hotel on Salisbury Road.

I rode down there early on the evening of the operation to assess the situation. That's when I bumped into Bruce Willis.

Next, I see Glen Close wandering around and taking photographs. Meanwhile, Canton Road is thronging with people. My boss is on scene controlling the road closures from the Marine Police HQ overlooking the venue. The crowds are building as a DJ wipes up the atmosphere as each celebrity arrives.

A giant Harley-Davidson motorcycle is positioned on the Regent Hotel's driveway. A cheer rose as Jean-Claude Camille François Van Varenberg, aka Jean-Claude Van Damme, appeared. He's tiny but, by all accounts, well-hard.

He mounted the bike, started the engine, and was about to head off to Canton Road—except that the "Muscles from Brussels" was not wearing a helmet. I stopped him.

After a short chat about the law, his minder produced a helmet. I then agree to escort him to the venue.

We set off in a small convoy, with me leading, Van Damme behind, and two constables at the rear. As we turned into Canton Road, the crowd went bonkers, and Van Damme milked it by pumping the air with his fist. Then, he shoots past me, drops his helmet in the road and roars up to the venue.

What a twat!

"Arrest him!" a voice is yelling through the radio.

A nimble Van Damme vaults off the bike to the red carpet to disappear into Planet Hollywood.

I can't move forward, surrounded by the cheering crowd. Meanwhile, Charlie Sheen arrives with a girl on each arm as Stallion glides along in a rickshaw. It's weird.

I confer with the boss. We agree it's not wise for me to haul Van Damme out. Yet, the Planet Hollywood PR people are fretting, recognising that Van Damme has caused some minor embarrassment.

"I'll arrest him when he comes out," I tell an ashen-faced PR woman.

That night, we saw nothing more of Van Damme. Before leaving, Jackie Chan thanked my officers and posed for pictures. A somewhat unsteady Glen Close gets helped into a taxi.

Meanwhile, my boys are having fun. Chatting with Bruce Willis is not something they get to do every day.

In this thankless task, I'm up against too many vehicles, poor infrastructure and inadequate parking. The geography doesn't help.

Tsim Sha Tsui is a natural bottleneck; the Cross Harbour Tunnel helps create daily tailbacks. Added to that is the ongoing construction work — as the joke goes, Hong Kong will look nice when it's finished!

The disconnect between what we could achieve and public expectations always vexed me. Nobody cares except that they can move about as quickly as possible and park anywhere. I soon learned that people in flash cars are selfish and entitled.

"Why isn't the traffic moving?"

"Because it blocked, Sir"

"Well, do something about it. I pay your wages." I have heard this phrase thousands of times.

Smile back while inside, thinking, "Work harder. I need more money."

For the most entitled who persisted a quick, "You appear to have a modified car, Sir. Do you have permission from the Transport Department for that spoiler? Please pull over up ahead."

That usually did the trick—not that I did it often. I'm not a vindictive individual, but some people need their self-entitlement deflated.

For most of the week, we spent our time trying to keep the traffic flowing. But come the weekends, the game changed. In a bizarre twist, our aim changed to slowing traffic flows on critical roads to defeat the illegal road racers—more on that in the next chapter.

My office is in the old Mongkok Police Station. The building dates from the 1920s and has creaking floorboards, high ceilings, and a distinctive colonial feel. I even have a fireplace in the office.

By now, I'm well versed in the etiquette of taking over a new unit. Rule number one: don't rush in and change things. The worst approach is to get all innovative without understanding the place's history.

Further, as the 'Chief Inspector of Enforcement and Control', I'm told my job is out on the streets. That suited me. Still, I already knew that keeping the traffic moving was an impossible task. We did what we could, which had a marginal impact at best.

My daily routine involves attending major traffic accidents, especially the deaths—they are never pleasant. I also lead operations against illegal taxis and tampered meters and deal with other traffic matters.

I am fortunate to have a competent crew of inspectors and station sergeants. The latter, who'd spent most of their careers in traffic, are the unit's backbone. I'm passing through in what will be a two-year posting, so it's always wise to take their counsel.

Most working days start with a meeting — morning prayers look at the last 24 hours to clear up outstanding issues and answer questions coming down the chain of command. Some bosses get triggered by exaggerated media reports with photographs taken out of context or commentaries based on misunderstandings or outright lies. It's a constant battle addressing this stuff.

Few things irked me more than the inane questions a moment of reflection could answer.

"Why was an officer not wearing his headgear at the traffic accident?"

"Well, because the press photographer caught him when he switched from his helmet to a soft cap."

Sometimes, the problem was intermediate commanders evoking the Regional Commander's name.

I caught out a superintendent who'd asked, "What was the delay in opening Canton Road?" he called to ask after a bus accident, "The boss wants to know."

Having got my answer, I couldn't reach the slippery super, so I called the boss directly.

"What are you talking about?" he snapped. I told him. Pause. I could hear his breathing down the phone.

"Mmmm. Leave that with me." I'm sure I wasn't winning friends.

After prayers, I'd undertake a quick patrol to show my face. Of course, the number of incidents drives the front-line officers' workload: accidents, road works and reports of obstructions. But, you could spend all day taking enforcement action and still only have a small impact.

There is no glamour in riding a 750 cc motorcycle around Kowloon. Picture this: heat, humidity, road crud, diesel fumes, and inattentive drivers combine in a tiring mix. Then along come downpours that turn the road surface into a skid pad. As the saying goes, "There are two types of traffic officers: those who had an accident and those waiting to have one."

Still, there were moments of excitement. Matters took a surprisingly dramatic turn in May 1992. Anita Mui, the "Madonna of the East", held her birthday party in a Kowloon karaoke club when trouble kicked off. She'd declined to sing with Wong Long-wai, a 14K triad member and movie producer. Having lost face, Wong slapped her.

The following evening, somebody slashed Wong in Wan Chai. One of the alleged assailants, Andely Chan Yiu-hing, also known as "the Tiger of Wan Chai", was a Sun Yee On triad. He and Mui had a close friendship. Chan also fancied himself as a race-car driver, so he was on our radar.

Two days later, recovering in hospital, someone walked in and executed Wong with a single shot to the head. Anita Mui immediately fled Hong Kong.

Trouble brewed between the 14K and Sun Yee On throughout 1992 and much of 1993. In response, the Regional Commander asked how units could help with a broader effort to disrupt the gangs. While traffic officers aren't usually involved in the direct fight against the triads, that was about to change.

A brainstorming session with my lads produced a couple of options. The boss agreed to our proposals. We'd start towing all the triad vehicles we could find illegally parked and set the motor vehicle examiners to work. Soon, CID provided a list of cars and locations. Off we went.

We began a disruption campaign at the scene of the initial incident in Kowloon Tong. We'd muster as many tow trucks as possible, wait for the triad boys to settle in the club and then start towing their cars. To keep the pressure on, we did this night after night. We bagged 42 cars one night, leaving their owners to find taxis.

When one of the tow truck drivers received threats, we identified the group responsible. They operated a repair shop in Tai Kok Tsui. For the next week, we visited them to ticket and tow anything outside their workshop. They needed to understand actions have consequences.

We later shifted focus to the Tsim Sha Tsui East area to disrupt the business of the triad car jockeys outside the nightclubs. The night before a public holiday or over a long weekend, we'd deploy 100-plus officers.

These tactics hit the triads in the pocket by discouraging their punters. Also, they struggled to move around as we hauled their cars away.

Occasionally, things became heated at the Homantin vehicle pound as the owners demanded their cars back. With 30 agitated drivers yelling at the pound staff, we'd front up with a PTU platoon in tow to ensure everyone behaved. The smart ones would keep their mouths shut, pay the impound fee and get their car back.

The less savvy drivers took to making a scene. That's silly, given that most had illegal modifications on their vehicles, which gave us the discretion to detain their cars. We ran this operation until late 1993. It was tiring and manpower-intensive, with overtime payments pushed to the limits. Yet, we'd made a point.

As Andy Chan remained a suspect in the murder of Wong, he kept a low profile. Then, on November 20, 1993, he finished second in the Macao Grand Prix but faced disqualification for modifications on his car. The following day, Chan died in a hail of bullets as he exited his Macau hotel. After that, things settled.

Some light relief came in 1994. On May 30, Hollywood came to Hong Kong. The opening of the movie-themed restaurant 'Planet Hollywood' was shaping up to be the night of the stars. A few A-listers are Sylvester Stallion, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Glen Close, Charlie Sheen, and Jackie Chan.

It was soon recognised that this lot would attract a considerable crowd that needed to be managed with road closures. The restaurant, sited on Canton Road, was the main focus, although many stars stayed at the nearby Regal Hotel on Salisbury Road.

I rode down there early on the evening of the operation to assess the situation. That's when I bumped into Bruce Willis.

Next, I see Glen Close wandering around and taking photographs. Meanwhile, Canton Road is thronging with people. My boss is on scene controlling the road closures from the Marine Police HQ overlooking the venue. The crowds are building as a DJ wipes up the atmosphere as each celebrity arrives.

A giant Harley-Davidson motorcycle is positioned on the Regent Hotel's driveway. A cheer rose as Jean-Claude Camille François Van Varenberg, aka Jean-Claude Van Damme, appeared. He's tiny but, by all accounts, well-hard.

He mounted the bike, started the engine, and was about to head off to Canton Road—except that the "Muscles from Brussels" was not wearing a helmet. I stopped him.

After a short chat about the law, his minder produced a helmet. I then agree to escort him to the venue.

We set off in a small convoy, with me leading, Van Damme behind, and two constables at the rear. As we turned into Canton Road, the crowd went bonkers, and Van Damme milked it by pumping the air with his fist. Then, he shoots past me, drops his helmet in the road and roars up to the venue.

What a twat!

"Arrest him!" a voice is yelling through the radio.

A nimble Van Damme vaults off the bike to the red carpet to disappear into Planet Hollywood.

I can't move forward, surrounded by the cheering crowd. Meanwhile, Charlie Sheen arrives with a girl on each arm as Stallion glides along in a rickshaw. It's weird.

I confer with the boss. We agree it's not wise for me to haul Van Damme out. Yet, the Planet Hollywood PR people are fretting, recognising that Van Damme has caused some minor embarrassment.

"I'll arrest him when he comes out," I tell an ashen-faced PR woman.

That night, we saw nothing more of Van Damme. Before leaving, Jackie Chan thanked my officers and posed for pictures. A somewhat unsteady Glen Close gets helped into a taxi.

Meanwhile, my boys are having fun. Chatting with Bruce Willis is not something they get to do every day.

Copyright © 2015