Marching, the Barber and Ammens Powder.

That first weekend, the local officers helped us settle in. They hung over us as we shopped for essentials in Wong Chuk Hang. They'd eyeball the stallholders to ensure they didn't rip us off with inflated prices. I soon learnt that Ammens powder is essential. It holds "prickly heat" at bay, while at least two showers a day was mandatory. Something of a shock for a body that got one bath a week in the UK!

Except for the odd room inspection, as officers we're spared mundane tasks. Our room boys cleaned and pressed the uniforms. Mind you. these 'boys' are in their 60s. My boots and shoes bulled, and then appear by magic each day beside my bed. We paid for this through our Mess bill, so money never changed hands: the whole system, seamless colonial efficiency.

The most wonderful surprise was the Saturday morning parade. We're seated to the rear of the empty parade ground, under the shade of trees, when the Pipe Band struck up. The parade square then fills as the massed ranks of trainees march out under a blistering tropical sun.

The Commandant appears in all his finery, accompanied by the Chief Drill and Musketry Instructor (CDMI). Rifle drills are performed with flawless precision to sharp orders.

Then the whole show exits the square to the sounds of the 'Happy Wanderer.' The scene that unfolded before us was straight out of the Raj. Stirring music, crashing feet in unison and orders echoing off the hills. And to cap it off, we retired to the Mess for a mid-morning gin and tonic.

That first week in Hong Kong consisted of kit issue, briefings, fitness tests, a tour of the territory and then sworn in as a police officer. Next, we did our first foot drill session, incurring the obligatory wrath of the instructors. Meanwhile, it was not long before the camp barbers got their grotty fingers on us for a scalping. My head bears the scars to this day.

A visit to the barbers was never a pleasant experience. Hygiene standards could be better. Hundreds of officers were getting haircuts every week, using four shavers. To add to our apprehension, a couple of the barbers were ex-heroin addicts. Shaky hands caused me to fear for my ears.

Except for the odd room inspection, as officers we're spared mundane tasks. Our room boys cleaned and pressed the uniforms. Mind you. these 'boys' are in their 60s. My boots and shoes bulled, and then appear by magic each day beside my bed. We paid for this through our Mess bill, so money never changed hands: the whole system, seamless colonial efficiency.

The most wonderful surprise was the Saturday morning parade. We're seated to the rear of the empty parade ground, under the shade of trees, when the Pipe Band struck up. The parade square then fills as the massed ranks of trainees march out under a blistering tropical sun.

The Commandant appears in all his finery, accompanied by the Chief Drill and Musketry Instructor (CDMI). Rifle drills are performed with flawless precision to sharp orders.

Then the whole show exits the square to the sounds of the 'Happy Wanderer.' The scene that unfolded before us was straight out of the Raj. Stirring music, crashing feet in unison and orders echoing off the hills. And to cap it off, we retired to the Mess for a mid-morning gin and tonic.

That first week in Hong Kong consisted of kit issue, briefings, fitness tests, a tour of the territory and then sworn in as a police officer. Next, we did our first foot drill session, incurring the obligatory wrath of the instructors. Meanwhile, it was not long before the camp barbers got their grotty fingers on us for a scalping. My head bears the scars to this day.

A visit to the barbers was never a pleasant experience. Hygiene standards could be better. Hundreds of officers were getting haircuts every week, using four shavers. To add to our apprehension, a couple of the barbers were ex-heroin addicts. Shaky hands caused me to fear for my ears.

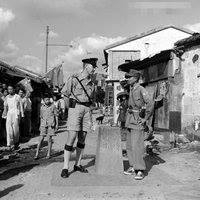

An Old Colonial Boy on the Border

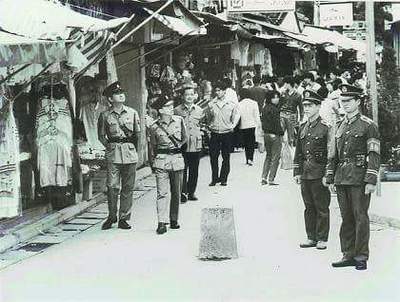

The highlight of that week was our trip to the border area, including Sha Tau Kok and Lau Fau Shan. Sha Tau Kok Village straddles the boundary between Hong Kong and the Mainland. A row of stones running down Chung Ying Street (literally China English Street) marks the border. With the Cold War still on and relations between the UK and China strained at times, Sha Tau Kok can be a tense place.

Indeed the People's Armed Police watched our every move. They shadowed our movements making great play of brandishing their machine guns. All rather sobering, especially when we're briefed on an incident that occurred on the 8th of July 1967. That day five Police Officers dead in a hail of gunfire. Then, with tensions high and unrest escalating, a Chinese militia group attacked Sha Tau Kok Police Station. Needless to say, this is a sensitive area.

Our next stop was a much more light-hearted affair. We met the redoubtable Bob Wilkinson, divisional commander Lau Fau Shan. Bob greeted us seated in an old armchair with a can of beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Nothing unusual. Except the chair was on the station roof, with a commanding view over Deep Bay towards Shekou. Moreover, it was evident from the many empty cans around him that he'd been there some time.

He briefed us on the surrounding area, including the illegal immigration and smuggling across Deep Bay. He displayed a complete grasp of his command. He named individual constables who'd made arrests over the past week—going through a long list. Bob was a dying breed who had served most of their career in the then remote New Territories. Rejecting Kowloon and Hong Kong as the 'bright lights', he was happiest living his life in the NT. Bob spoke fluent Cantonese. His men worshipped him. He'd taken on the role of godfather their kids, proving a ready source of advice on schooling. He was part mentor, part father-figure and all-around old-school gentleman.

In Force folklore, Bob was the last officer to receive a field promotion. The story behind this gives some insight into the man and his values. For promotion to Chief Inspector, you need to pass the Standard III law exams. These were then held twice a year down on Hong Kong Island. Working in a remote location, Bob faced something of a trek to the venue. He was upset when on arrival, the date was wrong.

The details got messed up somewhere along the way, and Bob sought an apology for that mix-up. As none was forthcoming, he declined to attend the exams. This impasse went on for over ten years. Then Commissioner Roy Henry intervened to give Bob a field promotion to Chief Inspector. Even so, years later, Bob was still upset that he'd been misled.

Bob was polite and insisted on proper manners. However, on one occasion in a pub, upset at the rudeness of a friend towards a barmaid, he intervened.

"If you persist with such rude behaviour, I must turn my back on you", he retorted.

I never got to work with Bob, although I met him a few times at social functions. Unfortunately, he died in 2008.

Indeed the People's Armed Police watched our every move. They shadowed our movements making great play of brandishing their machine guns. All rather sobering, especially when we're briefed on an incident that occurred on the 8th of July 1967. That day five Police Officers dead in a hail of gunfire. Then, with tensions high and unrest escalating, a Chinese militia group attacked Sha Tau Kok Police Station. Needless to say, this is a sensitive area.

Our next stop was a much more light-hearted affair. We met the redoubtable Bob Wilkinson, divisional commander Lau Fau Shan. Bob greeted us seated in an old armchair with a can of beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Nothing unusual. Except the chair was on the station roof, with a commanding view over Deep Bay towards Shekou. Moreover, it was evident from the many empty cans around him that he'd been there some time.

He briefed us on the surrounding area, including the illegal immigration and smuggling across Deep Bay. He displayed a complete grasp of his command. He named individual constables who'd made arrests over the past week—going through a long list. Bob was a dying breed who had served most of their career in the then remote New Territories. Rejecting Kowloon and Hong Kong as the 'bright lights', he was happiest living his life in the NT. Bob spoke fluent Cantonese. His men worshipped him. He'd taken on the role of godfather their kids, proving a ready source of advice on schooling. He was part mentor, part father-figure and all-around old-school gentleman.

In Force folklore, Bob was the last officer to receive a field promotion. The story behind this gives some insight into the man and his values. For promotion to Chief Inspector, you need to pass the Standard III law exams. These were then held twice a year down on Hong Kong Island. Working in a remote location, Bob faced something of a trek to the venue. He was upset when on arrival, the date was wrong.

The details got messed up somewhere along the way, and Bob sought an apology for that mix-up. As none was forthcoming, he declined to attend the exams. This impasse went on for over ten years. Then Commissioner Roy Henry intervened to give Bob a field promotion to Chief Inspector. Even so, years later, Bob was still upset that he'd been misled.

Bob was polite and insisted on proper manners. However, on one occasion in a pub, upset at the rudeness of a friend towards a barmaid, he intervened.

"If you persist with such rude behaviour, I must turn my back on you", he retorted.

I never got to work with Bob, although I met him a few times at social functions. Unfortunately, he died in 2008.