The night of Monday, 3rd May 1982 was to prove long and exciting. It foreshadowed the violence in Vietnamese camps that would flare for years. The platoon and I were patrolling Mongkok. A flash tasking message came through, "Proceed to Kai Tak Vietnamese Refugee Camp immediately."

A call to Kowloon Control added information. Fighting was underway inside the Camp. The details were sketchy. I'm to get there and deal with it.

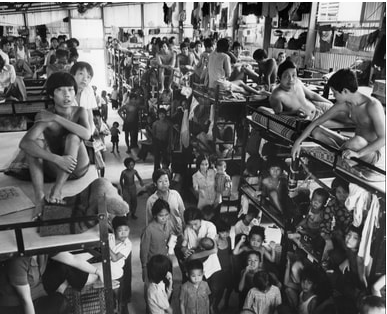

Housed at the former RAF Kai Tak base, the Camp is a cramped collection of buildings housing several thousand Vietnamese. That includes many children. The Camp has the well-resourced New Horizons School and a small medical centre. Operating as an 'open camp', the refugees could move in and out at will. The supposed curfew was never enforced by a lacklustre group of security guards on the gates.

South and North Vietnamese live in adjacent zones with no barrier between them. Given their history, this is a disaster waiting to happen.

My platoon was at near full strength with about 38 officers. We soon arrived outside on Kwun Tong Road to find a Superintendent on the scene. Fires were burning inside. Flames rose above the perimeter wall as thick black smoke billowed skywards.

Through the lone turnstile entrance, I could see groups of Vietnamese. Rushing back and forth, they brandished home-made clubs, knives and choppers. The Fire Services arrived to fight the fires. From the safety of Kwun Tong Road, they poured water over the perimeter wall. Traffic came to a halt as smoke obscured the road.

A few injured male Vietnamese lay curled up against the perimeter wall. I was looking for some guidance. Finally, the Superintendent announced he was going to get instructions. He mounted his Land Rover and was gone. We never saw him again that night.

My boys were now imposing control at the turnstile, helping women and kids through as they fled. A steady stream of ambulances conveyed the injured away. In the confusion, a constable is left holding a baby until the mother returns to claim it.

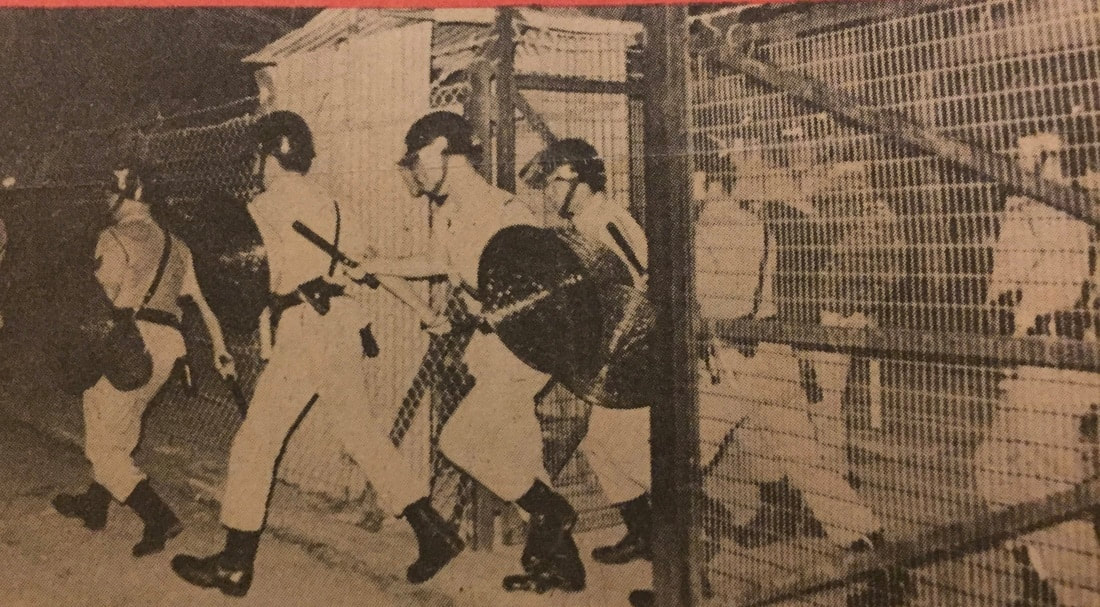

We'd arrived without riot gear, which limited our options. I had everyone draw their batons as we entered the turnstile gate single-file. This prolonged process meant forming a cordon line took time. Far from ideal, but we managed it.

Fortunately, the Vietnamese ignored us as they appeared more intent on attacking each other. At one point, I looked up in horror as a petrol bomb flew over our heads, landing against a nearby hut.

I'm thinking, "Bloody hell, this is serious." Then the reassuring figure of Jack Johnson, Regional Commander Kowloon, appeared. A no-nonsense copper from the old school of policing. He immediately began issuing orders.

"Separate the camp into two and isolate the opposing groups."

We are soon pushing back the Vietnamese into the huts.

My boys were a little hesitant until a Vietnamese took a swing at the imposing figure of Johnson. A swinging blow grazed Johnson's face. All hell then broke out. Batons were flying, and I was yelling, "Charge."

We barreled into a group of Vietnamese knocking them back.

Meanwhile, I could see a platoon of the Emergency Unit rushing to join us over my shoulder. Led by a Chief Inspector, they appeared from the opposite side of the Camp in a flying wedge. Cutting a path through the rioters, we soon had the upper hand. The Vietnamese fled.

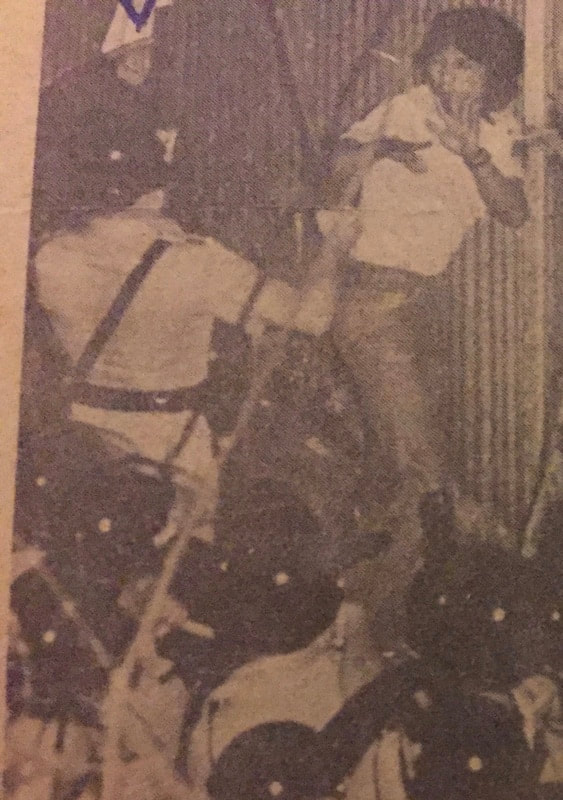

I found myself holding a pickaxe handle. Where this came from and how I came by it, I do not recall. But, I should point out that Inspectors don't carry batons. The next day my picture appeared in the newspapers. I was out of line, ahead of the platoon, swinging at a Vietnamese male.

The press coverage was favourable. The Vietnamese beat a few reporters; thus, any media sympathy for the refugees evaporated.

We later gained entry to the medical block. A group of nurses, expatriate and local ladies, had barricaded the doors with up-turned beds. Relieved to see us, they had stayed with their patients throughout the riot. I left a column guarding them and moved on.

It took about two hours to get things under control. By now, units from across Hong Kong converged on us in various states of readiness.

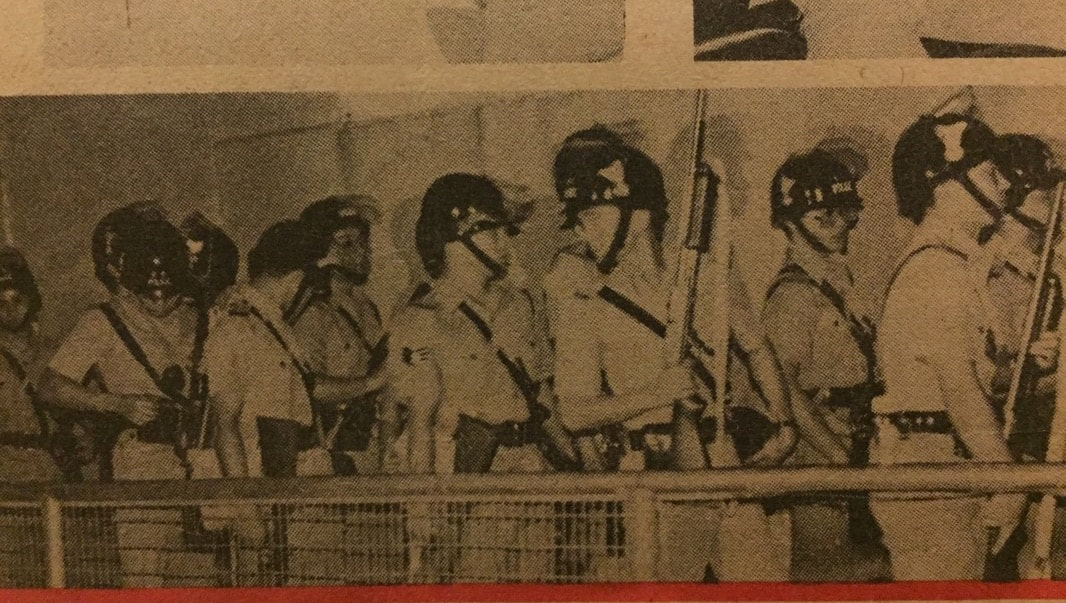

One keen inspector, arriving well after the action ceased, had his platoon in full riot gear blocking Kwun Tong Road. Such was the confusion of orders.

The next night, in a display of force, we returned with six companies of PTU and armoured cars. Again, we swept the Camp to pick up the ringleaders. We also hauled away a massive cache of home-made weapons and illicit alcohol stills. This operation was a template that was to repeat itself for many years to come.

Earlier in the evening, the enthusiasm of the inspector commanding the Saracens armoured car unit got the better of him. He attempted to breach a new entrance by ramming the Camp wall. However, the wall stood firm as one dented Saracen retreated.

Hong Kong is a refugee society. Yet animosity between China and Vietnam tempered any empathy for the Vietnamese refugees. Also, each day we handed hundreds of Chinese illegal immigrants back at the border.

Thus the treatment of Vietnamese did not play well with the local population. Blamed for increased petty crime, it was only a matter of time before the government acted.

On 1st July 1982, the closed camp policy started. Confinement was the fate of all new Vietnamese arrivals. The eventual aim is to resettle them overseas or seek their return to Vietnam. The Vietnamese population peaked in 1991 at 64,300.

Between 1979 and 1999, some 143,700 Vietnamese passed through screening to resettlement outside Hong Kong. Meanwhile, the 67,000 who failed to pass screening faced repatriation to Vietnam. A few went as volunteers, but most needed forced returns on planes. I was involved in these flights until 2000.

The resources and energy committed to dealing with the refugees distracted the Force from its core business. They tied up thousands of officers on guarding, escorting and feeding people. For many years other duties got pushed aside. As a result, the Triads and others enjoyed a period when their activities received less attention.

I grew up a fraction that night at Kai Tak Camp. That first encounter with a hostile crowd, armed with spears, is over-powering. Usually, a bit of reassurance from the more seasoned officers did the trick. Yet, I found myself lost for a moment. I'd never have admitted it at the time, putting on a brave face for the men.

In the following weeks, we mounted a high-profile presence in the Camp. We screened everyone going through the gates, seizing any contraband, including alcohol. We soon identified the ringleaders of the various fractions.

Then we set about making their life difficult. We followed them around. Disrupting their routine and making sure the other Vietnamese saw this. Anyone meeting with them was subject to search. We made them wait in the food line, giving priority to women and kids. The message was simple. You cause trouble, expect the same back.

In the meantime, the government was getting its act together. To defuse tension, with separation of North and South Vietnamese. Yet, this lesson was later forgotten and returned to haunt us at Shek Kong Camp in 1992.

Kai Tak Camp remained in operation until 1997. In its final years, it acted as a transit centre for refugees awaiting either repatriation or resettlement. However, the conditions in the camps caused many of us to question the government's approach.

Images of kids confined behind fences in tight unsanitary huts created a poor impression. It was challenging to witness kids growing up behind the wire. Was that the intent? Make it look harsh; then they'll stay away.

With my PTU attachment coming to an end, I was anticipating a post in the Emergency Unit. By temperament, I felt I was an ideal fit for that role. EU is the cavalry. EU mounts the response to all critical calls; robberies, burglary in progress. They charge in, take control, then buggers off after handing over to other duties—the least amount of paperwork, the most amount of action.

Headquarters had other ideas. I had nine months to run before my tour finished. I then had four months leave. I landed as a patrol commander at Kai Tak Airport.

A call to Kowloon Control added information. Fighting was underway inside the Camp. The details were sketchy. I'm to get there and deal with it.

Housed at the former RAF Kai Tak base, the Camp is a cramped collection of buildings housing several thousand Vietnamese. That includes many children. The Camp has the well-resourced New Horizons School and a small medical centre. Operating as an 'open camp', the refugees could move in and out at will. The supposed curfew was never enforced by a lacklustre group of security guards on the gates.

South and North Vietnamese live in adjacent zones with no barrier between them. Given their history, this is a disaster waiting to happen.

My platoon was at near full strength with about 38 officers. We soon arrived outside on Kwun Tong Road to find a Superintendent on the scene. Fires were burning inside. Flames rose above the perimeter wall as thick black smoke billowed skywards.

Through the lone turnstile entrance, I could see groups of Vietnamese. Rushing back and forth, they brandished home-made clubs, knives and choppers. The Fire Services arrived to fight the fires. From the safety of Kwun Tong Road, they poured water over the perimeter wall. Traffic came to a halt as smoke obscured the road.

A few injured male Vietnamese lay curled up against the perimeter wall. I was looking for some guidance. Finally, the Superintendent announced he was going to get instructions. He mounted his Land Rover and was gone. We never saw him again that night.

My boys were now imposing control at the turnstile, helping women and kids through as they fled. A steady stream of ambulances conveyed the injured away. In the confusion, a constable is left holding a baby until the mother returns to claim it.

We'd arrived without riot gear, which limited our options. I had everyone draw their batons as we entered the turnstile gate single-file. This prolonged process meant forming a cordon line took time. Far from ideal, but we managed it.

Fortunately, the Vietnamese ignored us as they appeared more intent on attacking each other. At one point, I looked up in horror as a petrol bomb flew over our heads, landing against a nearby hut.

I'm thinking, "Bloody hell, this is serious." Then the reassuring figure of Jack Johnson, Regional Commander Kowloon, appeared. A no-nonsense copper from the old school of policing. He immediately began issuing orders.

"Separate the camp into two and isolate the opposing groups."

We are soon pushing back the Vietnamese into the huts.

My boys were a little hesitant until a Vietnamese took a swing at the imposing figure of Johnson. A swinging blow grazed Johnson's face. All hell then broke out. Batons were flying, and I was yelling, "Charge."

We barreled into a group of Vietnamese knocking them back.

Meanwhile, I could see a platoon of the Emergency Unit rushing to join us over my shoulder. Led by a Chief Inspector, they appeared from the opposite side of the Camp in a flying wedge. Cutting a path through the rioters, we soon had the upper hand. The Vietnamese fled.

I found myself holding a pickaxe handle. Where this came from and how I came by it, I do not recall. But, I should point out that Inspectors don't carry batons. The next day my picture appeared in the newspapers. I was out of line, ahead of the platoon, swinging at a Vietnamese male.

The press coverage was favourable. The Vietnamese beat a few reporters; thus, any media sympathy for the refugees evaporated.

We later gained entry to the medical block. A group of nurses, expatriate and local ladies, had barricaded the doors with up-turned beds. Relieved to see us, they had stayed with their patients throughout the riot. I left a column guarding them and moved on.

It took about two hours to get things under control. By now, units from across Hong Kong converged on us in various states of readiness.

One keen inspector, arriving well after the action ceased, had his platoon in full riot gear blocking Kwun Tong Road. Such was the confusion of orders.

The next night, in a display of force, we returned with six companies of PTU and armoured cars. Again, we swept the Camp to pick up the ringleaders. We also hauled away a massive cache of home-made weapons and illicit alcohol stills. This operation was a template that was to repeat itself for many years to come.

Earlier in the evening, the enthusiasm of the inspector commanding the Saracens armoured car unit got the better of him. He attempted to breach a new entrance by ramming the Camp wall. However, the wall stood firm as one dented Saracen retreated.

Hong Kong is a refugee society. Yet animosity between China and Vietnam tempered any empathy for the Vietnamese refugees. Also, each day we handed hundreds of Chinese illegal immigrants back at the border.

Thus the treatment of Vietnamese did not play well with the local population. Blamed for increased petty crime, it was only a matter of time before the government acted.

On 1st July 1982, the closed camp policy started. Confinement was the fate of all new Vietnamese arrivals. The eventual aim is to resettle them overseas or seek their return to Vietnam. The Vietnamese population peaked in 1991 at 64,300.

Between 1979 and 1999, some 143,700 Vietnamese passed through screening to resettlement outside Hong Kong. Meanwhile, the 67,000 who failed to pass screening faced repatriation to Vietnam. A few went as volunteers, but most needed forced returns on planes. I was involved in these flights until 2000.

The resources and energy committed to dealing with the refugees distracted the Force from its core business. They tied up thousands of officers on guarding, escorting and feeding people. For many years other duties got pushed aside. As a result, the Triads and others enjoyed a period when their activities received less attention.

I grew up a fraction that night at Kai Tak Camp. That first encounter with a hostile crowd, armed with spears, is over-powering. Usually, a bit of reassurance from the more seasoned officers did the trick. Yet, I found myself lost for a moment. I'd never have admitted it at the time, putting on a brave face for the men.

In the following weeks, we mounted a high-profile presence in the Camp. We screened everyone going through the gates, seizing any contraband, including alcohol. We soon identified the ringleaders of the various fractions.

Then we set about making their life difficult. We followed them around. Disrupting their routine and making sure the other Vietnamese saw this. Anyone meeting with them was subject to search. We made them wait in the food line, giving priority to women and kids. The message was simple. You cause trouble, expect the same back.

In the meantime, the government was getting its act together. To defuse tension, with separation of North and South Vietnamese. Yet, this lesson was later forgotten and returned to haunt us at Shek Kong Camp in 1992.

Kai Tak Camp remained in operation until 1997. In its final years, it acted as a transit centre for refugees awaiting either repatriation or resettlement. However, the conditions in the camps caused many of us to question the government's approach.

Images of kids confined behind fences in tight unsanitary huts created a poor impression. It was challenging to witness kids growing up behind the wire. Was that the intent? Make it look harsh; then they'll stay away.

With my PTU attachment coming to an end, I was anticipating a post in the Emergency Unit. By temperament, I felt I was an ideal fit for that role. EU is the cavalry. EU mounts the response to all critical calls; robberies, burglary in progress. They charge in, take control, then buggers off after handing over to other duties—the least amount of paperwork, the most amount of action.

Headquarters had other ideas. I had nine months to run before my tour finished. I then had four months leave. I landed as a patrol commander at Kai Tak Airport.

Copyright © 2015