The Blue Berets - 1958 to 1997.

The Police Tactical Unit (PTU) was born of adversity. It has continued through a half-century to be at the forefront of all policing challenges. Sometimes applauded as Hong Kong's best insurance policy whilst also decried as a ruthless, aggressive unit at other times. The truth is more prosaic yet still compelling.

The media are apt to portray the 'Blue Berets' as an elite unit, with all the intrigue such a title confers. But, in truth, most Hong Kong Police officers can expect at least one PTU attachment in their career.

I was fortunate to serve as a Platoon Commander, Instructor, Chief Instructor, Company Commander and Deputy Commandant within the Police Tactical Unit. My aim here is to reflect on PTU's history as it evolved into the modern unit that plays a vital role in keeping Hong Kong safe.

I often hear voices asserting that the Royal Hong Kong Police and the PTU were much more benevolent in the colonial era. A cold examination of the evidence hardly supports this rose-tinted view. These opinions say more about the commentator's lack of understanding of history than the facts.

The events of October 1956 were the genesis of the PTU. On the 10th October 1956, celebrations of the 1911 October Revolution were underway. This anniversary inflamed simmering tensions between the Nationalist and Leftist communities, with each side vigilant and spoiling for trouble.

Enter a hapless and somewhat over-zealous housing official. He ordered the removal of a Nationalist flag, asserting that it was provocative. Shortly after the order was carried out, mobs spread from the Nationalist settlements in Kowloon. They looted shops and attacked a property known to belong to communist sympathisers. The so-called 'Double Tenth' riots rattled the colony for two days as disorder spread across Kowloon and Tsuen Wan.

Even the wife of the Swiss Consul got caught up in the riot with her taxi attacked. She died two days later. So severe did the situation become in Tsuen Wan that the British Army Queen's own 7th Hussars Regiment deployed. Yet, peace only returned after 59 deaths and over 500 injured.

Four people were later executed for their involvement in the killings.

The fact that the Hong Kong Police Force could not contain the situation caused grave concern. The force proved ill-equipped and psychologically unprepared. Whilst the level of violence caught the police off guard.

A single pamphlet was the only advice available to police commanders. It outlined the basic anti-riot formations and the kit needed, but beyond these scant details, commanders were on their own.

Moreover, a lack of transport and poor communications hampered any effort to mount a coordinated response. Some formations, such as the Emergency Units, proved enthusiastic, making a determined effort to curtail the violence. But alone, they could not disperse the rioters. Other units proved less robust.

In the aftermath, a working group was formed with the task of revamping the readiness of the force. Mr J.B. Lees and Mr Les Guyatt headed the team. They later became the first Commandant and Chief Instructor of the new Police Training Contingent (PTC). Both men had military experience, which had a bearing on the outcome of their work. First, a study of existing anti-riot units worldwide was undertaken. Next, details of equipment, tactics and the training needed came together.

By late 1957 a complete overhaul of anti-riot protocols was ready. It consisted of a single training depot new equipment and all officers to attend in-service training. The ultimate aim was to have a standardised response known to all officers.

For flexibility, the system envisaged the ability to slot officers into the anti-riot role as and when required. Yet, the proposals went further. A force-wide reserve structure came into being. This system meant resources could be called upon, coordinated and deployed at short notice. Work started with an abandoned army camp at Volunteer Slopes as the base and a $1,496,950 budget.

Unfortunately, the site was a run-down, mosquito-infested collection of huts lacking comforts, and thus needed some renovation. PTU officers would recognise this description well into the 1980s, as the upgrades were superficial at best.

Most buildings were Nissan huts, simple prefabricated steel structures with concrete supports. Designed in World War I and used by the military during World War II, the Nissan hut is a temporary structure. However, most remained in place until 1986.

The first 345 officers entered Volunteer Slopes to start training in February 1958. This initial cohort of volunteers underwent a six months residential course. The aim to form two companies proved ambitious.

The PTC struggled to secure enough volunteers, with the second company often left short-handed. Given the shortages, the company's size varied from three to five platoons—each platoon with 41 officers.

To ease the situation, non-volunteers came next. Immediately, officers pending discipline action found themselves heading to Fanling as units took the opportunity to get rid of troublemakers. Unfortunately, this did nothing for the quality of the companies and became a constant headache. Even into the 1980s, constant vigilance proved necessary to prevent this practice from happening again.

In the early years, officers from the land formations only went to the PTC for training. Then, starting in 1963, Marine Police Officers joined, forming a single platoon at a time. By the 1970s, the force expanded the PTC to eight companies with three platoons. On top of that, a reserve system operated six active companies and two dormant ones.Thus, eight deployable companies could be ready within days.

By 1980, six companies, each with four platoons, were the norm. This structure, with minor adjustments, remains in place to the present day.

Regimented training and tactics were the order of the day. Most actions followed strict drill movements. These methods harked back to the Romans as soldiers were 'drilled' until their responses became automatic. This approach serves a crucial purpose.

Under stress during a riot, with noise and threats acting as distractions, you revert to the training, an embedded rote response to orders. These same principles apply today, although with more flexibility.

With great foresight, the working group concluded that physical fitness was paramount. Only by honing fitness, could officers hope to remain committed and alert during extended operations. This founding principle crucial to the success of PTU. In later years the importance of fitness training grew. Although, as the cyber generation arrived, their lack of innate fitness threatened to compromise PTUs abilities.

The PTU course took on an outward-bound training programme to drive home the fitness message. Hill-walking, navigation, team-building, leadership challenges and assault courses, coupled with self-defence sessions, weight training and drills soon changed the officers. Plus, a natural team cohesion arose in this competitive environment, while awards such as the ‘Best Platoon Trophy’ fostered healthy competition.

The training culminated in a series of exercises. Officers faced an 'enemy' intent on stoning and out-manoeuvring them in a series of mock riots. Under stressful conditions, company and platoon commanders had to plan and execute operations. Meanwhile, the ever-vigilant staff provided constant distractions. These exercises concluded with thorough debriefs.

As officers reflected on their shortcomings and strengths, their tactical appreciation evolved. Whilst not always a pleasant experience, such debriefs proved cathartic. These methods taught 'Failing to plan is planning to fail'.

In the 1960s, not everyone supported these initiatives because PTU drew officers away from the front line for extended periods. Besides, a few questioned the merits of committing so much time and energy to training that officers may never need to use.

The events of April 1966 silenced these dissenting voices. The details of the Star Ferry riots, between 5th and 8th April 1966, I'll cover elsewhere. But, safe to say, a heady mix of social discontent, youth angst and hapless government policies all contributed. Sounds familiar.

The revamped anti-riot tactics proved their worth, law and order were re-established in the face of serious resistance. By the conclusion of the disturbance, 1,465 were arrested, with one person shot dead by the police. But the Star Ferry riot was only a foretaste of what was to come. Although it tested systems and procedures, it could hardly prepare the force for the sustained disorder of 1967.

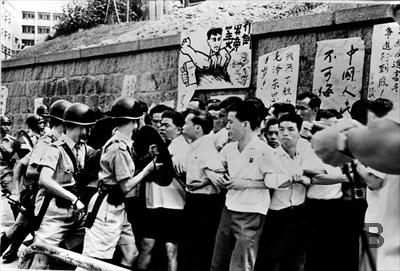

The origins of the 1967 riots are covered in another article. But, again, no single factor was at play. Instead, a potent interconnecting melee of issues swirled around. The unfolding 'Cultural Revolution', plus a slack economy and industrial disputes, played a part. Coupled with the revolutionary zeitgeist of the late 1960s, it all came together in an explosion of unrest.

An industrial dispute in April 1967 at a plastic flower factory in San Po Kong sparked events. This incident soon drew in local communist supporters. The dispute morphed into a conflict between colonial and mainland interests.

Rioting throughout the summer tested the police, who had to seek military support. Nonetheless, the Police Training Contingent proved its worth.

As the rioting subsided, a left-wing bombing campaign soon eroded public support for their cause. With Beijing taking a hands-off stance, the local leftists faced isolation. Arrests, convictions and deportations further undermined their ability to function by late 1967.

With calm returning in early 1968, the unit's role was subject to further review and evaluation. The value of anti-riot training was now well recognised. Moreover, the need to have a good part of the force trained was clear.

In 1969, the unit adopted the distinctive 'Blue Beret' as more comfortable headgear. It soon became the symbol of PTU. At first, worn only in training, it proved so popular with officers, therefore they began to wear it full-time. As a result, the press soon labelled the unit 'The Blue Berets'. The flash that sits behind the badge came later. The colours came from the puggaree around the topee worn by officers before World War II.

Come 1972, the now Police Tactical Unit (PTU) consisted of eight companies, although only six were formed at any time. On completion of training, companies returned to their respective regions for an operational attachment. Thus anti-riot knowledge spread throughout the force, as it became an integral part of an officer's career path.

Throughout the 1970s, the equipment and weapons of the PTU evolved as items became obsolete and new options emerged. The platoons also underwent a restructuring that saw each section with a different degree of force.

The baton charge was dropped as a tactical option in a notable move. The first section became the arrest section. This philosophy emerged to keep rioters at a distance, using stand-off weapons to disperse them. The second section, with smoke weapons, was the primary means of dispersal. The third section, with baton rounds, had a higher degree of force, and finally, the fourth section had lethal options with shotguns and rifles. This model was to remain unchanged with a few adaptations. Although the events of 'Occupy' saw the appearance of 'close-quarter' options.

In 1985 many PTU instructors, myself included, began pushing for a gradual relaxation of the formal drills. We perceived these to hamper flexibility in operations. After protracted consideration, things changed. Although to this day, the initial stages of training still include drill movements.These teach basic weapons handling and the positioning of officers. Drill also serves as a quick method of imposing 'team spirit' as officers soon bond in the face of the common adversary, the drill sergeant.

PTU faced a new challenge in the 1980s. The arrival of thousands of Vietnamese refugees overwhelmed the government's ability to house them. Moreover, Hong Kong's openness encouraged more arrivals, whilst the wider community feared increased crime. As a result, the government soon abandoned the initial 'open camp' policy.

Yet, closed camps created new difficulties as anger boiled up at the prolonged detention. Meanwhile, gangs developed, leading to large-scale fights over illegal alcohol sales or drugs.

I responded to the first Vietnamese riot in 1982 at the Kai Tak Open Camp. With strict instructions not to use smoke weapons, my platoon fought hand-to-hand to separate two groups of Vietnamese.

Unfortunately, the Vietnamese had their tactics; pushing women and children to the front. The men then hurled stones at us and used catapults to inflict injuries from cover. As dispersal was not an option with Vietnamese rioters confined in camps, PTU evolved more static tactics with long shields.

Kamp Ten training prepared the officers for operations in Vietnamese camps. In a simulated Vietnamese camp, an exercise commenced with forcing entry through a contested gate. A hail of rocks and real petrol bombs tested resolve.Once inside the camp, the officers had to sweep the ground, clearing buildings as they went. This fierce and exhausting exercise soon became the unofficial final test of PTU training. It took real courage and physical stamina to complete this gruelling exercise.

Unfortunately, CS smoke (tear gas) remained the only practical option at times in the Vietnamese camps. With children and women present, this was never an easy option. Moreover, the impact on surrounding communities did not endear us to the public. A riot at the Whitehead Camp had tear gas drifting through Ma On Shan.

No one relished such duties, given that innocent kids get caught up in the violence. Yet, it remained true that disorder needed suppression before matters escalated. In February 1992, 18 Vietnamese died at the Sek Kong Camp when a dispute over access to water flared. Again, it was south versus north Vietnamese. Outnumbered police officers could not contain the situation as huts burned. Only after 400 officers arrived and with the firing of 33 rounds of CS smoke, was control regained. But by then, it was too late.

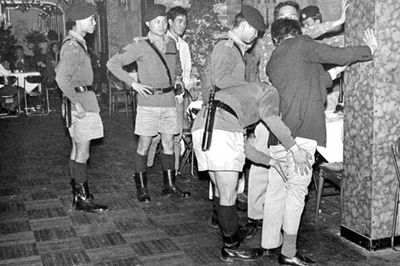

To help prevent trouble, the PTU were deployed to the Vietnamese camps to search for weapons, drugs and illegal alcohol. At times the haul of weapons was staggering. But, with plenty of time on their hands, the Vietnamese proved masters of innovation. Swords, spears, knives, darts and shields were produced in huge quantities.

They even produced gas masks from sanitary towels impregnated with charcoal. These were partially effective against our CS smoke. I always had respect for the Vietnamese, who displayed considerable ingenuity.

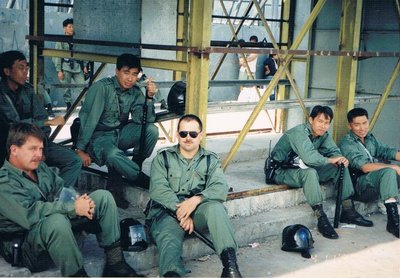

The role of the PTU gained added importance as 1997 approached. With unsettled times ahead, political sensitivities constrained the military's role. In recognition of this situation, the PTU needed investment in its future. In 1986, PTU moved into temporary accommodation whilst the Volunteer Slopes site was rebuilt.

The new PTU depot came online in 1990 with air-conditioned barracks, a sports complex, ranges, training areas and a radio workshop. But the regime remained the same—tight discipline, tough physical training, demanding practical exercises and an exhaustive pace.

From humble origins in a collection of old Nissan huts, the PTU is housed in a state-of-the-art complex today. And ready to face the challenges of the future.

The media are apt to portray the 'Blue Berets' as an elite unit, with all the intrigue such a title confers. But, in truth, most Hong Kong Police officers can expect at least one PTU attachment in their career.

I was fortunate to serve as a Platoon Commander, Instructor, Chief Instructor, Company Commander and Deputy Commandant within the Police Tactical Unit. My aim here is to reflect on PTU's history as it evolved into the modern unit that plays a vital role in keeping Hong Kong safe.

I often hear voices asserting that the Royal Hong Kong Police and the PTU were much more benevolent in the colonial era. A cold examination of the evidence hardly supports this rose-tinted view. These opinions say more about the commentator's lack of understanding of history than the facts.

The events of October 1956 were the genesis of the PTU. On the 10th October 1956, celebrations of the 1911 October Revolution were underway. This anniversary inflamed simmering tensions between the Nationalist and Leftist communities, with each side vigilant and spoiling for trouble.

Enter a hapless and somewhat over-zealous housing official. He ordered the removal of a Nationalist flag, asserting that it was provocative. Shortly after the order was carried out, mobs spread from the Nationalist settlements in Kowloon. They looted shops and attacked a property known to belong to communist sympathisers. The so-called 'Double Tenth' riots rattled the colony for two days as disorder spread across Kowloon and Tsuen Wan.

Even the wife of the Swiss Consul got caught up in the riot with her taxi attacked. She died two days later. So severe did the situation become in Tsuen Wan that the British Army Queen's own 7th Hussars Regiment deployed. Yet, peace only returned after 59 deaths and over 500 injured.

Four people were later executed for their involvement in the killings.

The fact that the Hong Kong Police Force could not contain the situation caused grave concern. The force proved ill-equipped and psychologically unprepared. Whilst the level of violence caught the police off guard.

A single pamphlet was the only advice available to police commanders. It outlined the basic anti-riot formations and the kit needed, but beyond these scant details, commanders were on their own.

Moreover, a lack of transport and poor communications hampered any effort to mount a coordinated response. Some formations, such as the Emergency Units, proved enthusiastic, making a determined effort to curtail the violence. But alone, they could not disperse the rioters. Other units proved less robust.

In the aftermath, a working group was formed with the task of revamping the readiness of the force. Mr J.B. Lees and Mr Les Guyatt headed the team. They later became the first Commandant and Chief Instructor of the new Police Training Contingent (PTC). Both men had military experience, which had a bearing on the outcome of their work. First, a study of existing anti-riot units worldwide was undertaken. Next, details of equipment, tactics and the training needed came together.

By late 1957 a complete overhaul of anti-riot protocols was ready. It consisted of a single training depot new equipment and all officers to attend in-service training. The ultimate aim was to have a standardised response known to all officers.

For flexibility, the system envisaged the ability to slot officers into the anti-riot role as and when required. Yet, the proposals went further. A force-wide reserve structure came into being. This system meant resources could be called upon, coordinated and deployed at short notice. Work started with an abandoned army camp at Volunteer Slopes as the base and a $1,496,950 budget.

Unfortunately, the site was a run-down, mosquito-infested collection of huts lacking comforts, and thus needed some renovation. PTU officers would recognise this description well into the 1980s, as the upgrades were superficial at best.

Most buildings were Nissan huts, simple prefabricated steel structures with concrete supports. Designed in World War I and used by the military during World War II, the Nissan hut is a temporary structure. However, most remained in place until 1986.

The first 345 officers entered Volunteer Slopes to start training in February 1958. This initial cohort of volunteers underwent a six months residential course. The aim to form two companies proved ambitious.

The PTC struggled to secure enough volunteers, with the second company often left short-handed. Given the shortages, the company's size varied from three to five platoons—each platoon with 41 officers.

To ease the situation, non-volunteers came next. Immediately, officers pending discipline action found themselves heading to Fanling as units took the opportunity to get rid of troublemakers. Unfortunately, this did nothing for the quality of the companies and became a constant headache. Even into the 1980s, constant vigilance proved necessary to prevent this practice from happening again.

In the early years, officers from the land formations only went to the PTC for training. Then, starting in 1963, Marine Police Officers joined, forming a single platoon at a time. By the 1970s, the force expanded the PTC to eight companies with three platoons. On top of that, a reserve system operated six active companies and two dormant ones.Thus, eight deployable companies could be ready within days.

By 1980, six companies, each with four platoons, were the norm. This structure, with minor adjustments, remains in place to the present day.

Regimented training and tactics were the order of the day. Most actions followed strict drill movements. These methods harked back to the Romans as soldiers were 'drilled' until their responses became automatic. This approach serves a crucial purpose.

Under stress during a riot, with noise and threats acting as distractions, you revert to the training, an embedded rote response to orders. These same principles apply today, although with more flexibility.

With great foresight, the working group concluded that physical fitness was paramount. Only by honing fitness, could officers hope to remain committed and alert during extended operations. This founding principle crucial to the success of PTU. In later years the importance of fitness training grew. Although, as the cyber generation arrived, their lack of innate fitness threatened to compromise PTUs abilities.

The PTU course took on an outward-bound training programme to drive home the fitness message. Hill-walking, navigation, team-building, leadership challenges and assault courses, coupled with self-defence sessions, weight training and drills soon changed the officers. Plus, a natural team cohesion arose in this competitive environment, while awards such as the ‘Best Platoon Trophy’ fostered healthy competition.

The training culminated in a series of exercises. Officers faced an 'enemy' intent on stoning and out-manoeuvring them in a series of mock riots. Under stressful conditions, company and platoon commanders had to plan and execute operations. Meanwhile, the ever-vigilant staff provided constant distractions. These exercises concluded with thorough debriefs.

As officers reflected on their shortcomings and strengths, their tactical appreciation evolved. Whilst not always a pleasant experience, such debriefs proved cathartic. These methods taught 'Failing to plan is planning to fail'.

In the 1960s, not everyone supported these initiatives because PTU drew officers away from the front line for extended periods. Besides, a few questioned the merits of committing so much time and energy to training that officers may never need to use.

The events of April 1966 silenced these dissenting voices. The details of the Star Ferry riots, between 5th and 8th April 1966, I'll cover elsewhere. But, safe to say, a heady mix of social discontent, youth angst and hapless government policies all contributed. Sounds familiar.

The revamped anti-riot tactics proved their worth, law and order were re-established in the face of serious resistance. By the conclusion of the disturbance, 1,465 were arrested, with one person shot dead by the police. But the Star Ferry riot was only a foretaste of what was to come. Although it tested systems and procedures, it could hardly prepare the force for the sustained disorder of 1967.

The origins of the 1967 riots are covered in another article. But, again, no single factor was at play. Instead, a potent interconnecting melee of issues swirled around. The unfolding 'Cultural Revolution', plus a slack economy and industrial disputes, played a part. Coupled with the revolutionary zeitgeist of the late 1960s, it all came together in an explosion of unrest.

An industrial dispute in April 1967 at a plastic flower factory in San Po Kong sparked events. This incident soon drew in local communist supporters. The dispute morphed into a conflict between colonial and mainland interests.

Rioting throughout the summer tested the police, who had to seek military support. Nonetheless, the Police Training Contingent proved its worth.

As the rioting subsided, a left-wing bombing campaign soon eroded public support for their cause. With Beijing taking a hands-off stance, the local leftists faced isolation. Arrests, convictions and deportations further undermined their ability to function by late 1967.

With calm returning in early 1968, the unit's role was subject to further review and evaluation. The value of anti-riot training was now well recognised. Moreover, the need to have a good part of the force trained was clear.

In 1969, the unit adopted the distinctive 'Blue Beret' as more comfortable headgear. It soon became the symbol of PTU. At first, worn only in training, it proved so popular with officers, therefore they began to wear it full-time. As a result, the press soon labelled the unit 'The Blue Berets'. The flash that sits behind the badge came later. The colours came from the puggaree around the topee worn by officers before World War II.

Come 1972, the now Police Tactical Unit (PTU) consisted of eight companies, although only six were formed at any time. On completion of training, companies returned to their respective regions for an operational attachment. Thus anti-riot knowledge spread throughout the force, as it became an integral part of an officer's career path.

Throughout the 1970s, the equipment and weapons of the PTU evolved as items became obsolete and new options emerged. The platoons also underwent a restructuring that saw each section with a different degree of force.

The baton charge was dropped as a tactical option in a notable move. The first section became the arrest section. This philosophy emerged to keep rioters at a distance, using stand-off weapons to disperse them. The second section, with smoke weapons, was the primary means of dispersal. The third section, with baton rounds, had a higher degree of force, and finally, the fourth section had lethal options with shotguns and rifles. This model was to remain unchanged with a few adaptations. Although the events of 'Occupy' saw the appearance of 'close-quarter' options.

In 1985 many PTU instructors, myself included, began pushing for a gradual relaxation of the formal drills. We perceived these to hamper flexibility in operations. After protracted consideration, things changed. Although to this day, the initial stages of training still include drill movements.These teach basic weapons handling and the positioning of officers. Drill also serves as a quick method of imposing 'team spirit' as officers soon bond in the face of the common adversary, the drill sergeant.

PTU faced a new challenge in the 1980s. The arrival of thousands of Vietnamese refugees overwhelmed the government's ability to house them. Moreover, Hong Kong's openness encouraged more arrivals, whilst the wider community feared increased crime. As a result, the government soon abandoned the initial 'open camp' policy.

Yet, closed camps created new difficulties as anger boiled up at the prolonged detention. Meanwhile, gangs developed, leading to large-scale fights over illegal alcohol sales or drugs.

I responded to the first Vietnamese riot in 1982 at the Kai Tak Open Camp. With strict instructions not to use smoke weapons, my platoon fought hand-to-hand to separate two groups of Vietnamese.

Unfortunately, the Vietnamese had their tactics; pushing women and children to the front. The men then hurled stones at us and used catapults to inflict injuries from cover. As dispersal was not an option with Vietnamese rioters confined in camps, PTU evolved more static tactics with long shields.

Kamp Ten training prepared the officers for operations in Vietnamese camps. In a simulated Vietnamese camp, an exercise commenced with forcing entry through a contested gate. A hail of rocks and real petrol bombs tested resolve.Once inside the camp, the officers had to sweep the ground, clearing buildings as they went. This fierce and exhausting exercise soon became the unofficial final test of PTU training. It took real courage and physical stamina to complete this gruelling exercise.

Unfortunately, CS smoke (tear gas) remained the only practical option at times in the Vietnamese camps. With children and women present, this was never an easy option. Moreover, the impact on surrounding communities did not endear us to the public. A riot at the Whitehead Camp had tear gas drifting through Ma On Shan.

No one relished such duties, given that innocent kids get caught up in the violence. Yet, it remained true that disorder needed suppression before matters escalated. In February 1992, 18 Vietnamese died at the Sek Kong Camp when a dispute over access to water flared. Again, it was south versus north Vietnamese. Outnumbered police officers could not contain the situation as huts burned. Only after 400 officers arrived and with the firing of 33 rounds of CS smoke, was control regained. But by then, it was too late.

To help prevent trouble, the PTU were deployed to the Vietnamese camps to search for weapons, drugs and illegal alcohol. At times the haul of weapons was staggering. But, with plenty of time on their hands, the Vietnamese proved masters of innovation. Swords, spears, knives, darts and shields were produced in huge quantities.

They even produced gas masks from sanitary towels impregnated with charcoal. These were partially effective against our CS smoke. I always had respect for the Vietnamese, who displayed considerable ingenuity.

The role of the PTU gained added importance as 1997 approached. With unsettled times ahead, political sensitivities constrained the military's role. In recognition of this situation, the PTU needed investment in its future. In 1986, PTU moved into temporary accommodation whilst the Volunteer Slopes site was rebuilt.

The new PTU depot came online in 1990 with air-conditioned barracks, a sports complex, ranges, training areas and a radio workshop. But the regime remained the same—tight discipline, tough physical training, demanding practical exercises and an exhaustive pace.

From humble origins in a collection of old Nissan huts, the PTU is housed in a state-of-the-art complex today. And ready to face the challenges of the future.

Copyright © 2015