Hong Kong's Best Insurance

By August 1991, it's time for another rotation. One advantage of this constant job switching is the variety of roles you experience. Moreover, you can get from under a difficult boss at some stage.

I had no such worries because I was heading back to the biggest boys club in town — the Police Tactical Unit staff. I'm to command Training Team 2, based in our superb new depot at Fanling. They've selected me, and within certain limits, I get to put together my team.

Gone are the crappy Nissan huts from yesteryear, replaced with state-of-the-art facilities. Air-conditioned classrooms, video walls, shooting ranges, a gym, a drill square and a 'close-quarter-battle-house'. Topping it all off was the Officer's Mess with accommodation. The depot is a fitting representation of the expanding role and importance of the PTU. But, with 1997 on the horizon, significant changes are coming.

For starters, more officers need to pass through PTU as the number of companies increases each year. As a consequence, the turn-over of officers from the Regions went up. At times the Regions struggled to identify enough qualified people. Not everyone appeared keen on the role, with a few avoiding PTU by failing the medical.

A certain amount of folklore existed around this topic; some believed eating specific hot peppers did the trick. Also, high blood pressure is easy to achieve by large doses of caffeine.

The Force grew wise to this, making PTU a mandatory posting for anyone seeking promotion or service in specialist units. That soon put paid to the shirkers. Over time, with adequate monitoring, very few could dip out.

The other significant change was taking control of the frontier closed area from the military. This task entailed new skills, with a need to revamp training.

Under British rule, the Police and military cooperated daily at a local level. They'd provide helicopters, specialist kit and other helpful support. But given the sensitivities, that wouldn't be so straightforward after 1997. Thus, we needed to beef up our capabilities and capacity to handle the unforeseen.

As if this wasn't enough, the ongoing disturbances in the Vietnamese camps kept us busy. Then, in a regular occurrence, questions arose about our tactics. The dispersal methods used on-streets disorders didn't apply in the Vietnamese camps. They had nowhere to go. Moreover, the presence of women and children, including infants, weighed on everyone's minds. More on that later.

My role as a Chief Instructor involved taking a company from form-up through 12-weeks training. For the officers and NCOs, PTU augmented their leadership development. That included tactical appreciation, operational planning and briefing practice.

Then, when the whole company of 170 formed up, we'd introduce riot drills, sweeping, cordoning and various other roles. All training focused on the practical aspects of the job; each phase concluded with an exercise to assess progress.

With a morning PT session thrown in, this is an arduous regime that soon sees the weight drop off and improves fitness levels. As a result, everyone leaves PTU training lighter.

The final exercise would see the whole company deployed. With rising tensions in the Vietnamese camps, the scenario could involve a 'forced entry' to a barricaded camp and then sweep for weapons. Having acquired new long shields, we'd evolved our tactics and introduced the 'tortoise'.

The Vietnamese were savvy opponents. They'd frequently barricade gates to prevent us access. Officers approaching a gate faced a hail of stones and the occasional petrol bomb. Spears, arrows and knives also came our way, as a cottage industry existed converting bed frames and window sills into weapons.

The 'tortoise' concept we'd borrowed from a long line of warriors. In simple terms, it's a shield roof with more shields encircling the team. If set-up well, with careful coordination, the 'tortoise' is fortress-like.

We'd mock-up of a Vietnamese camp called 'Kamp Ten' for these exercises. You could sense the tension in the build-up as the company deployed on the ground as PTU staff ramped up the violence. Thick smoke, darkness and the noise of the 'enemy' at the gate all added to the confusion.

Then with grit and determination, the tortoise formed up. Coordinating the movement was a challenge made no easier by a hail of rocks and petrol bombs. Inching forward, covered by volleys of tear gas pushing the enemy back, they'd reach the gate. Then using bolt-cutters, access the camp.

They'd then charge forward to form a cordon line. Then, if synchronised well, the rest of the company would stream in to start a sweep. You needed real courage and physical determination to complete this gruelling exercise.

Towards the end of these exercises, staff remained vigilant. Scuffles between the company and the officers playing the enemy were few but did occur. With their blood up, some individuals needed calming.

Understandably, the use of tear gas in the confined space of a Vietnamese camp raised concerns. Although, the clever men who sat in judgement couldn't make their minds up.

After the Shek Kong fire in 1992, the Kempster Report suggested using more tear gas earlier to contain trouble. Then an inquiry by Justices of the Peace in 1994, following rioting at Whitehead, stated we'd used too much tear gas.

The Justices took evidence from NGOs, the Vietnamese refugees, the UNHCR and the government. They then examined footage of the rioting. Next, they considered alternatives, including the use of water cannons or dropping water bombs from helicopters.

Finally, the Justices concluded that tear gas was the best option to regain control of violent situations. They rightly deduced that 'hand-to-hand' fighting or the use of other techniques could produce more injuries. This lesson needed relearning time and time again.

Yet, they recommended that the order to use tear gas must come from a 'senior commander' — not specified who. It was thus introducing a delay in the process—the sort of delay that led to Shek Kong 1992.

When police officers face a hostile or rioting crowd, the stark reality is that they have few options. Summarised best as:-

Take your pick. None of these options is ideal, pretty or guarantees no injuries on either side. Plus, never forget that the Police must restore order — that's a duty.

With large crowds, dispersal remains the best and preferred option in most instances, with tear gas as the minimal 'use of force'. Fire and move, fire and move. And, don't make arrests unless planned — because arrests slow down the dispersal. Get the rioters moving and off the street — keep the momentum going. I'd welcome anyone to debate that approach.

These tried and tested tactics remained the cornerstone of our anti-riot strategy during my service. And no matter what weapons you use, be it water cannon or projectiles, that philosophy applies.

For the Vietnamese camps, with no dispersal possible, the options are far fewer. Mostly, we hit them with tear gas until they'd had enough and gave up.

Having said that, once repatriations started, young males would barricade themselves in huts. These people required an extraction team. Invariably this would lead to some 'hand-to-hand' fighting. PTU staff would fit the 'Red Man' suit to play the resisting Vietnamese to prepare the officers for this.

The 'Red Man' suit comes billed as "offers excellent protection and mobility for defensive tactics training…". Yet, the entry teams appeared infused when faced with PTU Staff playing the 'enemy'. My bruises attest to their vigour.

In the 2019 disturbances, the use of tear gas prevented many injuries. For this reason, the opposition sought to stop it because they recognised its potency. They even persuaded the UK to halt supplies of tear gas to Hong Kong.

Although, the UK had no such reservations when we used it on the Vietnamese refugees. Moreover, the UK didn't foresee removing tear gas as an option meant the Police only had a more lethal option. Fortunately, other sources of tear gas existed, and operations continued uninterrupted. Strange, the Brits have no issue with firing tear gas at their people.

With the wind-down of the British military, the Police resumed coverage of the frontier between Hong Kong and the Mainland. Illegal immigration across the line was still an issue, although not on the scale seen in the 1960s and 1970s.

A substantial fence, watchtowers, lighting, patrols and ambushes all acted as deterrents. But, in the end, the economic boom on the Mainland removed the impetus to test your luck by crossing to Hong Kong. After all, you could make a better living in Shenzhen.

By 1991, a trickle of illegals sought to make their move each night. Working from sensor alerts and with night vision equipment, army ambushes could catch some at the fence. Others would fall to the ambushes set as back-stops.

Initially, the PTU companies were trained to adopt the same tactics as the army. The Field Patrol Detachment team introduced the role during the finals stages of PTU training. Then gradually, it dawned on us we could do better than the military. Their tactics evolved from military actions of ambushes and covertness.

And while playing soldiers was fun playing soldiers, police officers needed strategies that leveraged our skills.

For starters, given that we spoke Cantonese, we had greater access to intelligence. Besides, villagers fearful of crime would often provide information. Likewise, we soon discovered the limited routes chosen by the illegals funnelled into choke points.

Officers posted at the local bus stop or an intersection produced as many arrests as an ambush position a night. Over time, we reduced the military approach of fixed ambushes and moved into detection, with a rapid response unit ready to deploy.

During the transition period, as Police took over the sector, the odd cock-up tested nerves. At Sha Tau Kok, with few physical reminders of the boundary line, you needed extra care. One PTU company orderly took a wrong turn, crossed over and found himself surrounded by the People's Armed Police. He's returned later that day, a little shaken but otherwise unharmed.

As new companies rotated through the sector, such mishaps were not uncommon. Usually, the fault lay with an inattentive police driver. The Chinese side sent the offender back with a few choice words. But it worked both ways.

They'd occasionally come over to our side. But, in the end, we all grew relaxed about this — after all, making an official report caused more questions and a panic that sometimes reached London.

Throughout the latter part of 1991, training continued with the odd deployment to Vietnamese camps on weapon searches. Then at Chinese New Year February 1992, unprecedented violence in the Shek Kong Vietnamese Camp resulted in 24 dead and over 128 injured. Amongst the dead were 12 children, including a one-year-old. This incident remains Hong Kong's most significant murder case.

The huge Shek Kong camp housed 9,000 Vietnamese on a closed runway. The Police Force ran the place with help from various NGOs and a contingent of the UNHCR.

Shek Kong is no holiday camp, yet it offers the basics. The Vietnamese slept in bunk beds with communal showers and kitchens. Divided into sections, the Vietnamese moved through controlled security gates.

Also, having learnt nothing from the 1982 Kai Tak Camp riot, the government opted to place north and south Vietnamese in adjacent sections. At various times during the day, to deliver food and clean-up, the two groups mixed. Also, they traded, including illicit alcohol.

With a traditional simmering animosity between the groups and disputes over alcohol sales, trouble was coming.

Compounding the situation was the Chinese New Year holidays. Again, a reduced police presence meant officers were stretched.

On February 3, running battles broke out between the southerners and the northerners. The northerners mounted the initial attack on the southerners. As Police sought to intervene, outnumbered officers withdrew to the main gate. The gates between the sections remained open.

Under attack, some 200 northerners retreated to hut Nos 6, which is then surrounded and firebombed. Scenes of terror and mayhem ensue. Finally, a police party forced entry to push back the rioters. It's all over in 30 minutes.

At home, I received the call to turn out. First, I went to the PTU Fanling base to collect my gear before making my way to Shek Kong, accompanied by a team of PTU instructors. We'd grabbed extra tear gas grenades from the PTU armoury. As we arrived on the scene, the trouble was over, with a weapon search underway.

Immediately we mounted patrols on the perimeter, as traumatised North Vietnamese wanted out of the camp. Meanwhile, Gurkha's formed an outer cordon providing a deterrent to anyone seeking to flee. While the high perimeter fence was intact, attempts at breaching were everywhere.

Later, we filtered people through the main gates, searching them for weapons before going to a holding area.

In the command post, it was evident that several police commanders were in shock. Exhausted, already a few were blaming themselves for not doing more. One Expat officer wandered off and back into the camp to mingle with the refugees. Alerted to this, I and others extracted him because the mood was less than calm.

The next day we escorted 2,000 Vietnamese out of Shek Kong for transfer to Chi Ma Wan. Kids with dead stares and trembling mothers gave witness to the strain—the quiet of the island contrasting with the mayhem at Shek Kong.

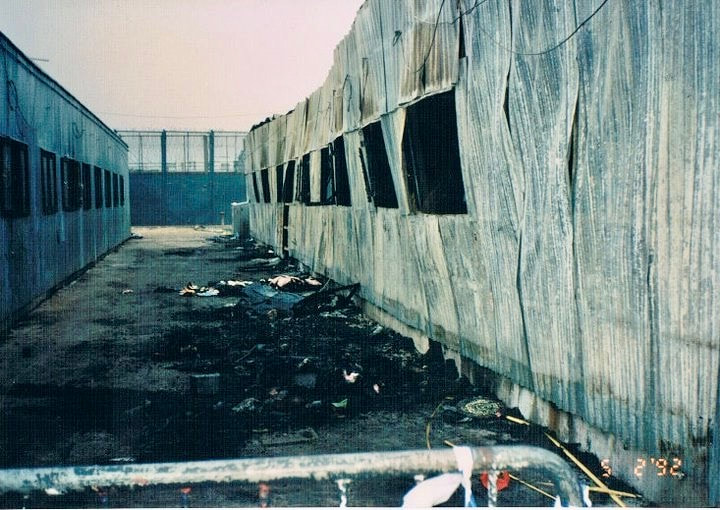

Meanwhile, crime officers faced the gruesome tasks of recovering the bodies for forensics. Many died from smoke inhalation as they scrambled to get out of the burning hut. They'd squeezed through gaps between the tin walls and the concrete base. I'd visited the scene once during the night and came away shaken.

An independent inquiry followed as 169 Vietnamese faced charges. Then in November 1994, jail terms totalling 78 years came down on the six main culprits for manslaughter and rioting.

High Court Justice Michael Kempster's report blamed events on overcrowding, disputes over alcohol sales, and the Police's failure to respond to escalating fighting. He cited the police withdrawal as 'officers losing the initiative'. Further, he went on, 'if the Police had used their substantial stock of tear gas … the tragedy might well have been avoided'.

Many of us viewed the criticism with mixed feelings. Commanders hung back because of limited manpower, an unclear picture, and fear of causing more injuries. However, on previous occasions, we'd received stinging criticism for being too quick to act.

The rote complaining by the UNHCR of 'over-aggressive policing' in Vietnamese camps made international headlines. It was thus surprising to hear individual UNHCR officials demand we protect them as they went about their business in the camps.

With the benefit of hindsight, the armchair critics had clarity that's not afforded officers on the ground. Operating at night with conflicting information isn't straightforward. Plus, few of the commentators had ever faced an angry mob. So I viewed the accusation against officers as absurd.

Much of the blame must fall to the government. Putting feuding Vietnamese in adjacent sections was a recipe for disaster. They then made matters worse by over-crowding. Then when it went wrong, the Police scrambled to contain the violence.

The thankless work in Vietnamese camps carried on. Meanwhile, civil liberties lawyers, keen to score a Police scalp, hovered in the background. While some were doubtless well-meaning, others came with a plan of self-publicity.

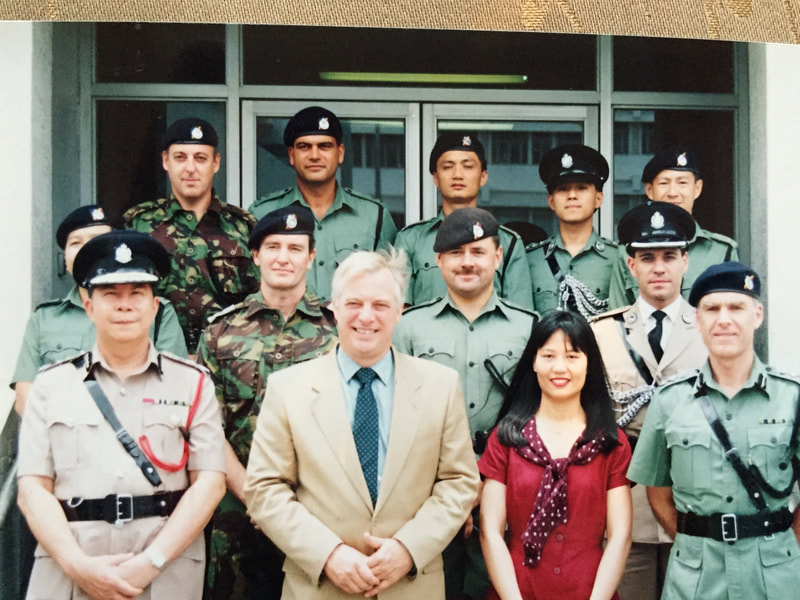

Tear smoke came up again when the new Governor, Chris Patten, visited PTU in June 1992. He was doing the rounds, getting to know units in the Police Force. I briefed him on our weapons, getting him to fire a baton shell.

Accompanied by his aides, we sat down for lunch in the Officer's Mess. Over lunch, Patten's bagman (Martin Dinham, I believe) challenged us, "Isn't tear gas dangerous?"

He went on to assert it was indiscriminate and disproportionate, as he roundly questioned our methods. I sensed he'd prepared his points, rattling them off as Patten remained silent. Then, he heaped praise on the British Police, who he asserted didn't need to use tear gas.

A quick lesson on tactics and the merits of tear gas as against beating people with batons followed. I may have mentioned the inability of the British Police to control riots in any pro-active sense. Because standing behind shields, allowing a mob to throw stuff, does not constitute an adequate response.

Anyway, within months, Patten and his bagman were back at PTU. They came to praise us for handling several Vietnamese camp riots—no more questions about tear gas.

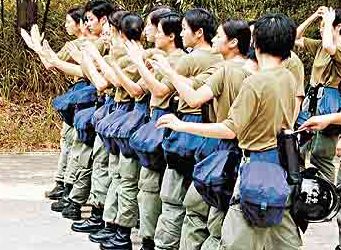

In mid-1992, I started training the first all-female company, "Tango". Duties in the Vietnamese camps meant we handled large numbers of women and children. With repatriation flights beginning, we'd need the ladies.

Adapting and modifying the training to meet the needs of "Tango" proved a quick process. I envisaged they'd be dealing with passive resistors and the lower levels of violence. We didn't foresee they'd play a fighting role on the frontline, although they later did.

In media statements at the time, I commented: "the ladies learnt faster than their male colleagues". That's still the case.

Later, ladies integrated into the PTU Companies. It is difficult to understand the resistance that this faced when first proposed. In truth, while not as physically robust as the men, the ladies fitted in well.

Often overlooked is the crucial coaching role played by PTU. Through vigorous and realistic exercises and then deployments, PTU nurtures leaders.

One Mess night, I heard said, "PTU is Hong Kong's best insurance". Over the years, I grew to recognise this statement as a real insight. Why so? PTU played a leading role and continues to play a leading role in keeping Hong Kong safe and stable.

Some question the methods used by PTU; others bleat for political reasons seeking to discredit a formidable opponent. Yet, PTU remains steadfast.

I had no such worries because I was heading back to the biggest boys club in town — the Police Tactical Unit staff. I'm to command Training Team 2, based in our superb new depot at Fanling. They've selected me, and within certain limits, I get to put together my team.

Gone are the crappy Nissan huts from yesteryear, replaced with state-of-the-art facilities. Air-conditioned classrooms, video walls, shooting ranges, a gym, a drill square and a 'close-quarter-battle-house'. Topping it all off was the Officer's Mess with accommodation. The depot is a fitting representation of the expanding role and importance of the PTU. But, with 1997 on the horizon, significant changes are coming.

For starters, more officers need to pass through PTU as the number of companies increases each year. As a consequence, the turn-over of officers from the Regions went up. At times the Regions struggled to identify enough qualified people. Not everyone appeared keen on the role, with a few avoiding PTU by failing the medical.

A certain amount of folklore existed around this topic; some believed eating specific hot peppers did the trick. Also, high blood pressure is easy to achieve by large doses of caffeine.

The Force grew wise to this, making PTU a mandatory posting for anyone seeking promotion or service in specialist units. That soon put paid to the shirkers. Over time, with adequate monitoring, very few could dip out.

The other significant change was taking control of the frontier closed area from the military. This task entailed new skills, with a need to revamp training.

Under British rule, the Police and military cooperated daily at a local level. They'd provide helicopters, specialist kit and other helpful support. But given the sensitivities, that wouldn't be so straightforward after 1997. Thus, we needed to beef up our capabilities and capacity to handle the unforeseen.

As if this wasn't enough, the ongoing disturbances in the Vietnamese camps kept us busy. Then, in a regular occurrence, questions arose about our tactics. The dispersal methods used on-streets disorders didn't apply in the Vietnamese camps. They had nowhere to go. Moreover, the presence of women and children, including infants, weighed on everyone's minds. More on that later.

My role as a Chief Instructor involved taking a company from form-up through 12-weeks training. For the officers and NCOs, PTU augmented their leadership development. That included tactical appreciation, operational planning and briefing practice.

Then, when the whole company of 170 formed up, we'd introduce riot drills, sweeping, cordoning and various other roles. All training focused on the practical aspects of the job; each phase concluded with an exercise to assess progress.

With a morning PT session thrown in, this is an arduous regime that soon sees the weight drop off and improves fitness levels. As a result, everyone leaves PTU training lighter.

The final exercise would see the whole company deployed. With rising tensions in the Vietnamese camps, the scenario could involve a 'forced entry' to a barricaded camp and then sweep for weapons. Having acquired new long shields, we'd evolved our tactics and introduced the 'tortoise'.

The Vietnamese were savvy opponents. They'd frequently barricade gates to prevent us access. Officers approaching a gate faced a hail of stones and the occasional petrol bomb. Spears, arrows and knives also came our way, as a cottage industry existed converting bed frames and window sills into weapons.

The 'tortoise' concept we'd borrowed from a long line of warriors. In simple terms, it's a shield roof with more shields encircling the team. If set-up well, with careful coordination, the 'tortoise' is fortress-like.

We'd mock-up of a Vietnamese camp called 'Kamp Ten' for these exercises. You could sense the tension in the build-up as the company deployed on the ground as PTU staff ramped up the violence. Thick smoke, darkness and the noise of the 'enemy' at the gate all added to the confusion.

Then with grit and determination, the tortoise formed up. Coordinating the movement was a challenge made no easier by a hail of rocks and petrol bombs. Inching forward, covered by volleys of tear gas pushing the enemy back, they'd reach the gate. Then using bolt-cutters, access the camp.

They'd then charge forward to form a cordon line. Then, if synchronised well, the rest of the company would stream in to start a sweep. You needed real courage and physical determination to complete this gruelling exercise.

Towards the end of these exercises, staff remained vigilant. Scuffles between the company and the officers playing the enemy were few but did occur. With their blood up, some individuals needed calming.

Understandably, the use of tear gas in the confined space of a Vietnamese camp raised concerns. Although, the clever men who sat in judgement couldn't make their minds up.

After the Shek Kong fire in 1992, the Kempster Report suggested using more tear gas earlier to contain trouble. Then an inquiry by Justices of the Peace in 1994, following rioting at Whitehead, stated we'd used too much tear gas.

The Justices took evidence from NGOs, the Vietnamese refugees, the UNHCR and the government. They then examined footage of the rioting. Next, they considered alternatives, including the use of water cannons or dropping water bombs from helicopters.

Finally, the Justices concluded that tear gas was the best option to regain control of violent situations. They rightly deduced that 'hand-to-hand' fighting or the use of other techniques could produce more injuries. This lesson needed relearning time and time again.

Yet, they recommended that the order to use tear gas must come from a 'senior commander' — not specified who. It was thus introducing a delay in the process—the sort of delay that led to Shek Kong 1992.

When police officers face a hostile or rioting crowd, the stark reality is that they have few options. Summarised best as:-

- Retreat and ignore it;

- Allow the riot to continue, but cordon if possible;

- Seek to negotiate with the rioters (yep, right)

- By your presence, seek to deter and disperse them;

- Advance on the rioter and engage in 'hand-to-hand' fighting;

- Use stand-off weapons such as tear gas, and seek to disperse them.

Take your pick. None of these options is ideal, pretty or guarantees no injuries on either side. Plus, never forget that the Police must restore order — that's a duty.

With large crowds, dispersal remains the best and preferred option in most instances, with tear gas as the minimal 'use of force'. Fire and move, fire and move. And, don't make arrests unless planned — because arrests slow down the dispersal. Get the rioters moving and off the street — keep the momentum going. I'd welcome anyone to debate that approach.

These tried and tested tactics remained the cornerstone of our anti-riot strategy during my service. And no matter what weapons you use, be it water cannon or projectiles, that philosophy applies.

For the Vietnamese camps, with no dispersal possible, the options are far fewer. Mostly, we hit them with tear gas until they'd had enough and gave up.

Having said that, once repatriations started, young males would barricade themselves in huts. These people required an extraction team. Invariably this would lead to some 'hand-to-hand' fighting. PTU staff would fit the 'Red Man' suit to play the resisting Vietnamese to prepare the officers for this.

The 'Red Man' suit comes billed as "offers excellent protection and mobility for defensive tactics training…". Yet, the entry teams appeared infused when faced with PTU Staff playing the 'enemy'. My bruises attest to their vigour.

In the 2019 disturbances, the use of tear gas prevented many injuries. For this reason, the opposition sought to stop it because they recognised its potency. They even persuaded the UK to halt supplies of tear gas to Hong Kong.

Although, the UK had no such reservations when we used it on the Vietnamese refugees. Moreover, the UK didn't foresee removing tear gas as an option meant the Police only had a more lethal option. Fortunately, other sources of tear gas existed, and operations continued uninterrupted. Strange, the Brits have no issue with firing tear gas at their people.

With the wind-down of the British military, the Police resumed coverage of the frontier between Hong Kong and the Mainland. Illegal immigration across the line was still an issue, although not on the scale seen in the 1960s and 1970s.

A substantial fence, watchtowers, lighting, patrols and ambushes all acted as deterrents. But, in the end, the economic boom on the Mainland removed the impetus to test your luck by crossing to Hong Kong. After all, you could make a better living in Shenzhen.

By 1991, a trickle of illegals sought to make their move each night. Working from sensor alerts and with night vision equipment, army ambushes could catch some at the fence. Others would fall to the ambushes set as back-stops.

Initially, the PTU companies were trained to adopt the same tactics as the army. The Field Patrol Detachment team introduced the role during the finals stages of PTU training. Then gradually, it dawned on us we could do better than the military. Their tactics evolved from military actions of ambushes and covertness.

And while playing soldiers was fun playing soldiers, police officers needed strategies that leveraged our skills.

For starters, given that we spoke Cantonese, we had greater access to intelligence. Besides, villagers fearful of crime would often provide information. Likewise, we soon discovered the limited routes chosen by the illegals funnelled into choke points.

Officers posted at the local bus stop or an intersection produced as many arrests as an ambush position a night. Over time, we reduced the military approach of fixed ambushes and moved into detection, with a rapid response unit ready to deploy.

During the transition period, as Police took over the sector, the odd cock-up tested nerves. At Sha Tau Kok, with few physical reminders of the boundary line, you needed extra care. One PTU company orderly took a wrong turn, crossed over and found himself surrounded by the People's Armed Police. He's returned later that day, a little shaken but otherwise unharmed.

As new companies rotated through the sector, such mishaps were not uncommon. Usually, the fault lay with an inattentive police driver. The Chinese side sent the offender back with a few choice words. But it worked both ways.

They'd occasionally come over to our side. But, in the end, we all grew relaxed about this — after all, making an official report caused more questions and a panic that sometimes reached London.

Throughout the latter part of 1991, training continued with the odd deployment to Vietnamese camps on weapon searches. Then at Chinese New Year February 1992, unprecedented violence in the Shek Kong Vietnamese Camp resulted in 24 dead and over 128 injured. Amongst the dead were 12 children, including a one-year-old. This incident remains Hong Kong's most significant murder case.

The huge Shek Kong camp housed 9,000 Vietnamese on a closed runway. The Police Force ran the place with help from various NGOs and a contingent of the UNHCR.

Shek Kong is no holiday camp, yet it offers the basics. The Vietnamese slept in bunk beds with communal showers and kitchens. Divided into sections, the Vietnamese moved through controlled security gates.

Also, having learnt nothing from the 1982 Kai Tak Camp riot, the government opted to place north and south Vietnamese in adjacent sections. At various times during the day, to deliver food and clean-up, the two groups mixed. Also, they traded, including illicit alcohol.

With a traditional simmering animosity between the groups and disputes over alcohol sales, trouble was coming.

Compounding the situation was the Chinese New Year holidays. Again, a reduced police presence meant officers were stretched.

On February 3, running battles broke out between the southerners and the northerners. The northerners mounted the initial attack on the southerners. As Police sought to intervene, outnumbered officers withdrew to the main gate. The gates between the sections remained open.

Under attack, some 200 northerners retreated to hut Nos 6, which is then surrounded and firebombed. Scenes of terror and mayhem ensue. Finally, a police party forced entry to push back the rioters. It's all over in 30 minutes.

At home, I received the call to turn out. First, I went to the PTU Fanling base to collect my gear before making my way to Shek Kong, accompanied by a team of PTU instructors. We'd grabbed extra tear gas grenades from the PTU armoury. As we arrived on the scene, the trouble was over, with a weapon search underway.

Immediately we mounted patrols on the perimeter, as traumatised North Vietnamese wanted out of the camp. Meanwhile, Gurkha's formed an outer cordon providing a deterrent to anyone seeking to flee. While the high perimeter fence was intact, attempts at breaching were everywhere.

Later, we filtered people through the main gates, searching them for weapons before going to a holding area.

In the command post, it was evident that several police commanders were in shock. Exhausted, already a few were blaming themselves for not doing more. One Expat officer wandered off and back into the camp to mingle with the refugees. Alerted to this, I and others extracted him because the mood was less than calm.

The next day we escorted 2,000 Vietnamese out of Shek Kong for transfer to Chi Ma Wan. Kids with dead stares and trembling mothers gave witness to the strain—the quiet of the island contrasting with the mayhem at Shek Kong.

Meanwhile, crime officers faced the gruesome tasks of recovering the bodies for forensics. Many died from smoke inhalation as they scrambled to get out of the burning hut. They'd squeezed through gaps between the tin walls and the concrete base. I'd visited the scene once during the night and came away shaken.

An independent inquiry followed as 169 Vietnamese faced charges. Then in November 1994, jail terms totalling 78 years came down on the six main culprits for manslaughter and rioting.

High Court Justice Michael Kempster's report blamed events on overcrowding, disputes over alcohol sales, and the Police's failure to respond to escalating fighting. He cited the police withdrawal as 'officers losing the initiative'. Further, he went on, 'if the Police had used their substantial stock of tear gas … the tragedy might well have been avoided'.

Many of us viewed the criticism with mixed feelings. Commanders hung back because of limited manpower, an unclear picture, and fear of causing more injuries. However, on previous occasions, we'd received stinging criticism for being too quick to act.

The rote complaining by the UNHCR of 'over-aggressive policing' in Vietnamese camps made international headlines. It was thus surprising to hear individual UNHCR officials demand we protect them as they went about their business in the camps.

With the benefit of hindsight, the armchair critics had clarity that's not afforded officers on the ground. Operating at night with conflicting information isn't straightforward. Plus, few of the commentators had ever faced an angry mob. So I viewed the accusation against officers as absurd.

Much of the blame must fall to the government. Putting feuding Vietnamese in adjacent sections was a recipe for disaster. They then made matters worse by over-crowding. Then when it went wrong, the Police scrambled to contain the violence.

The thankless work in Vietnamese camps carried on. Meanwhile, civil liberties lawyers, keen to score a Police scalp, hovered in the background. While some were doubtless well-meaning, others came with a plan of self-publicity.

Tear smoke came up again when the new Governor, Chris Patten, visited PTU in June 1992. He was doing the rounds, getting to know units in the Police Force. I briefed him on our weapons, getting him to fire a baton shell.

Accompanied by his aides, we sat down for lunch in the Officer's Mess. Over lunch, Patten's bagman (Martin Dinham, I believe) challenged us, "Isn't tear gas dangerous?"

He went on to assert it was indiscriminate and disproportionate, as he roundly questioned our methods. I sensed he'd prepared his points, rattling them off as Patten remained silent. Then, he heaped praise on the British Police, who he asserted didn't need to use tear gas.

A quick lesson on tactics and the merits of tear gas as against beating people with batons followed. I may have mentioned the inability of the British Police to control riots in any pro-active sense. Because standing behind shields, allowing a mob to throw stuff, does not constitute an adequate response.

Anyway, within months, Patten and his bagman were back at PTU. They came to praise us for handling several Vietnamese camp riots—no more questions about tear gas.

In mid-1992, I started training the first all-female company, "Tango". Duties in the Vietnamese camps meant we handled large numbers of women and children. With repatriation flights beginning, we'd need the ladies.

Adapting and modifying the training to meet the needs of "Tango" proved a quick process. I envisaged they'd be dealing with passive resistors and the lower levels of violence. We didn't foresee they'd play a fighting role on the frontline, although they later did.

In media statements at the time, I commented: "the ladies learnt faster than their male colleagues". That's still the case.

Later, ladies integrated into the PTU Companies. It is difficult to understand the resistance that this faced when first proposed. In truth, while not as physically robust as the men, the ladies fitted in well.

Often overlooked is the crucial coaching role played by PTU. Through vigorous and realistic exercises and then deployments, PTU nurtures leaders.

One Mess night, I heard said, "PTU is Hong Kong's best insurance". Over the years, I grew to recognise this statement as a real insight. Why so? PTU played a leading role and continues to play a leading role in keeping Hong Kong safe and stable.

Some question the methods used by PTU; others bleat for political reasons seeking to discredit a formidable opponent. Yet, PTU remains steadfast.

Copyright © 2015